Respiratory diseases in pigs have multiple causes, with the involvement of different factors: infectious agents, nutrition and predisposing management factors such as temperature, ventilation, population density, facilities conditions, etc.

The most relevant infectious agents described in the Porcine Respiratory Disease Complex (PRDC) include:

- Bacteria: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Haemophilus parasuis, Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcus suis and Mycoplasma hyorhinis.

- Virus: PRRSv, Influenza virus, PCV2, Respiratory Coronavirus.

- Parasites: Metastrongylus spp.

The laboratory analysis provides detailed information on the presence of the infectious agents involved, which makes it possible to make a better decision regarding the implementation of effective measures. Depending on the availability and purpose of the analysis (clinical case diagnosis or farm monitoring), different types of samples can be analysed (Table 1.)

TABLE 1: Type of respiratory sample, advantages and disadvantages.

| TYPE OF SAMPLE | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

| Lungs |

|

|

| Bronchoalveolar lavages or bronchial scraping |

|

|

| Oral fluids |

|

|

| Nasal swabs |

|

|

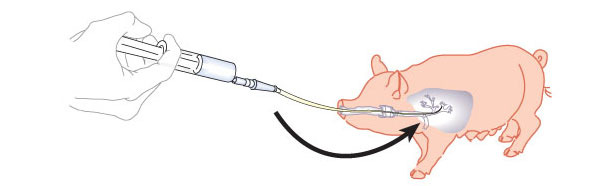

Bronchoalveolar lavages and bronchial scraping (Figure 1) are very useful in the case of a respiratory problems with animals showing respiratory signs, such as cough or dyspnea, and no casualties. It allows the sampling of a significant number of animals grouping them by age, barn or production stage. Provide accurate information about the microorganisms present in the lungs.

Figure 1. Sketch showing a bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial scraping

The methodology is simple and quick once the person obtaining the samples is familiar with it. The following video shows the technique. Access can be oral or nasal and, depending on the type of access and age of the animal, different types of catheter need to be available.

The protocol for bronchial scraping is the same as the one for the lavage, except for the introduction of saline. Once the catheter has reached the bronchi, the catheter is removed and its distal part cut into a tube containing 1-2 ml of sterile saline solution.

In order to assess the effectiveness of each sampling technique for the detection of the aforementioned infectious agents, a study was carried out comparing the results obtained from bronchoalveolar lavages and bronchial scraping, using the real-time PCR technique (qPCR).

The study was conducted on a group of 68 animals from three different farms. This group included animals in the main stages of production: suckling piglets (n = 1), weaned piglets (n = 11), sows (n = 17), internal replacements (n = 12) and fatteners between 30 kg and 100 kg (n = 27).

Bronchoalveolar lavages and bronchial scraping were taken from each animal. Subsequently, an automatic extraction system was used to obtain the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) of each sample, and qPCR kits were used for molecular detection of the following parameters: PRRSV, PCV2, influenza A virus, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Mycoplasma hyorhinis, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Haemophilus parasuis and Streptococcus suis. All samples with a Cq < 38 value were considered positive.

All infectious agents were detected in both types of samples; the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: qPCR results of the parameters analysed in both sample types expressed as percentages of positive samples.

| Parameter | LAVAGE | SCRAPING |

| PRRSV | 31.1 | 30.7 |

| PCV2 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| Influenza A virus | 2.6 | 5.3 |

| M. hyopneumoniae | 26.0 | 29.6 |

| M. hyorhinis | 62.3 | 77.3 |

| A. pleuropneumoniae | 16.9 | 22.7 |

| H. parasuis | 44.2 | 46.7 |

| S. suis | 50.0 | 87.84 |

Given the small size of the sample, the results were compared statistically using a Fischer exact test. Only significant differences were found for the detection of M. hyorhinis and S. suis. Detection in the bronchial scraping sample was higher for these parameters. No significant differences were observed in the detection levels for the other parameters studied.

Many field veterinarians find bronchial scraping a less invasive and, above all, simpler sampling method than bronchoalveolar lavage. In addition to these advantages, the equivalent or even better detection capacity of bronchial scraping for the main pathogens of interest in the PRDC must be considered. Subsequent studies should be carried out with bigger sample sizes, to analyse in detail other variables such as age of the animals and quantitative results in the appropriate agents. However, we could conclude that scraping is an effective sampling method and it can be established as a valid alternative to bronchoalveolar lavages.