There has been a lot of interest in the Smithfield Foods purchase by China’s Shuanghui International, the largest pork processor in China. Reaction to the purchase fell out largely along predictable lines. Individuals and NGOs that generally favor free markets cheered the sale and sent letters of support to the policy-makers responsible for evaluating and providing approval. Those who see international trade as ultimately bad for the domestic producer sent letters of opposition. Part of the concern was that by taking the company private, the transparency of future activities is limited since some of the reporting mandated from a publically traded company is no longer required. In addition, some saw a new source of funding for the expansion of large scale agriculture to be a threat to the family farm worldwide and were concerned that China would gain access to U.S. animal production and processing technology, some of which was alleged to have been funded by public sources. The other concerns typically mentioned were related to food safety issues and whether or not the standards enforced upon heavily regulated U.S. food companies would continue to be observed.

China has for many years seen the handwriting on the wall with respect to its own future demand for everything from food to consumer goods to basic resources like coal, oil, precious metals and ores of every description. Inflationary consumer goods prices, especially for food and basic necessities and worse yet, shortages and outages are the quickest paths to policy change (at the least) and more likely regime change. China has not been readily open to accepting these kinds of risks, partly from its experience in history and partly because it realizes that a weakening United States is likely to lead in the coming years to more global instability. Being dependent on day-to-day trading in the global markets for necessities makes a country with demand as large as China’s especially vulnerable to “food as a weapon” strategies. To combat this, China has been for many years using its accumulated balance of trade advantages in factory goods to acquire long term global sources, through purchase or century long leases, enabling access to the basic resources and food inputs needed to meet its growing future demand. A consumer demand that is growing, not because population is growing (it isn’t by very much and will go negative in a decade or so) or because demographics are evolving (a similar bubble to the U.S. baby boom is currently working its way through the population pyramid), but because per capita income is increasing.

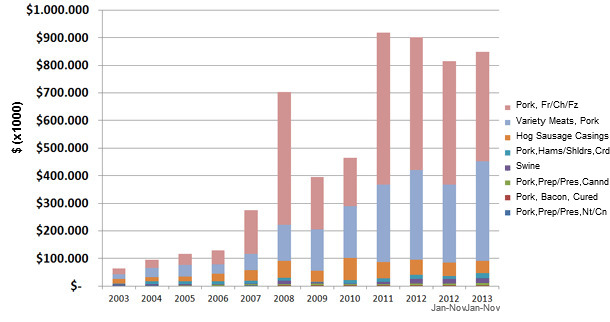

United States Pork Exports to China and Hong Kong 2003-2013 FAS Annual Export Data (000,s $)

Those in the United States who believed that suddenly the flow of all processed pork from the various Smithfield plants would take a trip to the west coast and depart in shipping containers to China are likely to be surprised (disappointed). There are some who believed that the export of pork to China by Smithfield Foods would at the least require substantial replacement in the domestic market of the United States and therefore increase the demand for domestically produced hogs. This increased demand would provide an opportunity for both expansion and at least temporarily, enhanced market prices. Some of that of course will happen but the ending equilibrium will surprise people who have not thought much about the other possibilities.

There are a couple of things that make a massive export scenario unlikely. First, while Shuanghui International may have demand for the whole carcass output and a great distribution network in China, it is more likely that various parts of the hog, both the carcass and the offal are more in demand than others, so shipping whole carcasses can lead to some pricing problems. Responding to this partial carcass and pork product demand (shipping too many of one part) can result in profit optimization problems as it makes for an unbalanced offering remaining in the United States and can subject the processor to less than favorable overall pricing for the remainder. This is partially ameliorated by the fact that the Chinese demand is quite diverse and does not match the U.S. consumer demand.

For instance, if a large scale Japanese packer were to emerge in the United States, buy live pigs and send most of the loins and bellies to Japan or other global destinations, the plant mix remaining would not offer the major meat buyers in the United States a full line of cuts and parts. This means the plant would have to market the parts remaining with a substantial discount. While some of that can be successfully done with hams and sides, it leaves the remaining cuts even more unbalanced (compared to a full carcass offering) and that usually means discounting to move all the meat remaining.

While there seems little doubt that the purchase of Smithfield will mean it will export more meat both to China and to some new customers for which the Chinese will provide entree, it does not seem likely that the level will be taken to the point of disrupting relationships with Smithfield’s best domestic customers. More likely, Shuanghui sees Smithfield as simply one of many future acquisitions and new operations it plans to both make and build in China, the United States and worldwide. Having Smithfield gives it the ability to grow globally using the tremendous capability and proven track record of Smithfield Foods. Shuanghui International’s goal is the Chinese government’s goal, to acquire long-term, low cost sources of China’s favorite meat by forming long term, low risk, globally coherent pork and agricultural resources chains and they are well on way to that goal.