Farm description

The fattening farm was located in south-western Poland. The farmer breeds only fatteners, which come from different herds in Denmark. Pigs arrive at 10 weeks of age, just after the nursery period.

The farm consists of 4 identical buildings where fattening of 7000 animals takes place. The farm is stocked every 5 months. One building houses the animals (about 1750) which are purchased from one farrow-to-wean farm and are characterised by a similar health status. All fattening buildings had identical living conditions, as well as the same feeding, management and veterinary rules; the only difference was in service.

The environmental conditions may be considered good. In the units the "all in – all out" procedure was maintained. In the herd, routine prophylactic vaccinations against PCV2, mycoplasmal pneumonia of swine, erysipelas, and pleuropneumonia were carried out in the farm.

The health status of the herd is moderate and mainly depends on the health status of the herd of origin.

- PAR- negative, NPAR – positive

- PRRSV: negative

- Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae: positive

- Aujeszky’s disease: negative

- Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae: positive

- SIV: positive

Case description

At the end of April 2015, in the early morning hours, a total of 1750 piglets, each weighing about 18-22 kg, arrived at the farm in three swine transport trucks. The pigs from each vehicle, in the number of 600 animals, were placed in three separate halls in one of the swineries.

The previously prepared halls had been washed, disinfected through fumigation, and then with dry disinfectants. The interior of the buildings was heated up to 22°C. At the same time the other buildings housed about 3 400 piglets which had been transported to the site earlier.

The signs of the disease only occurred in one group of animals (about 600) located in a single hall.

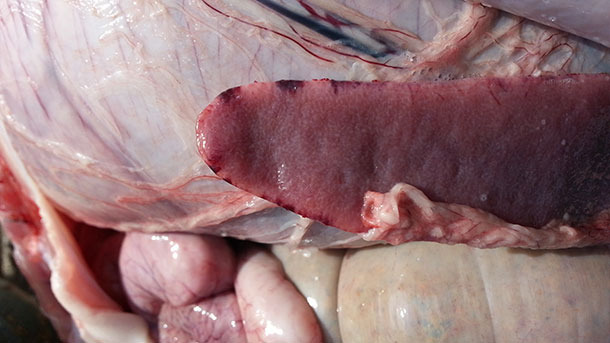

After about 10 hours since stocking, diarrheal symptoms occurred (loose stool, yellow-green to cocoa-deep red, at times with traces of blood). An autopsy of one animal, deceased on the first day, was conducted. Haemorrhagic enterocolitis with mucosal oedema (Fig. 1), enlarged spleen and haemorrhagic mesentery were observed.

Figure 1. Haemorrhagic enterocolitis with mucosal oedema.

Amoxicillin and colistin were administered to the whole group. Also, enrofloxacin injections were recommended to all pigs with clinical signs (diarrhoea).

On the second day, about 11:00 a.m., 6 more pigs from the same hall were declared dead, and further 10 showed the signs including cyanosis and limb paralysis. At about 01:00 p.m., 60 pigs were observed to have the following symptoms: apathy, recumbence, frothy vomit with undigested contents, as well as neurological symptoms such as "aimless wandering", adopting a dog sitting position combined with characteristic head movements, and pressing against obstacles.

Loose, yellow-green to brown faeces were present in all pens. The internal body temperature of the animals with clinical symptoms ranged from 38,5 to 41°C. During the autopsy varying degrees of the following were observed: cyanosis of the abdominal walls, peripheral splenic infarction (Fig. 2-3), increased amount of bloody cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and catarrhal and haemorrhagic enterocolitis.

Figure 2-3. Peripheral splenic infarction.

On the third day the symptoms were observed in 15 more pigs. Some of them showed neurological clinical signs deemed as "induced by injections" – they began to shake, fell down, and were unable to stand up. That day a total of 10 more animals died.

On the fourth day, only five "new" pigs showed clinical signs. The pigs in the pens became more lively, although all the animals in which neurological symptoms had been observed continued to remain apathetic (video).

The following samples of the materials were sent for testing: stool, brain swabs, CSF, blood, smears from the abdominal cavity, intestine, and lung. The treatment based on administration of antibiotics did not bring therapeutic results.

Lab results

Table 1. Directions of research, materials, methods and results of laboratory tests.

| Direction | Haemophilus parasuis | ASF | Classical Swine Fever | Colibacillosis | Ileitis | Swine dysentery | Aujeszky’s disease | Streptococcus suis |

| Materials | Swabs, CSF | Lymph nodes, blood, spleen | Lymph nodes, blood, spleen | Faeces | Faeces | Faeces | Serum | CSF |

| Methods | PCR | PCR | PCR | Bacteriology, PCR (stx2e, F18, F4) | PCR | PCR | ELISA | Bacteriology |

| Results | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative |

Table 2. Paired results of levels of sodium in CSF and serum (mmol/l) of pigs with nervous symptoms.

| No. of sick pig | CSF (cerebro-spinal fluid) | Serum |

| 1 | 148 | 135 |

| 2 | 173 | 153 |

| 3 | 175 | 147 |

| 4 | 171 | 134 |

| 5 | 160 | 136 |

The mean sodium concentration in the sera of animals with the symptoms was 141 mmol/l and did not differ significantly from the sodium concentration in the sera of the asymptomatic pigs - 137 mmol/l.

However, the concentration of sodium in cerebrospinal fluid of dead animals was 165 mmol/l, being significantly higher than sodium concentration in their serum. It was also markedly higher than sodium concentration determined in the CSF of healthy pigs - 139 mmol/l in the studies conducted by Oswieler and Hurd (1974).

Conclusions

In conclusion, out of 600 animals that were placed in the same hall, about 80 animals showed clinical symptoms, with neurological signs observed in 40. In total, 35 pigs died during the first two weeks, with 30 animals deceased within the first three days. Among the animals with neurological symptoms, only 7 survived.

On the basis of clinical signs and the autopsies as well as laboratory testing, it can be claimed that the most likely cause of the symptoms occurring at the farm was sodium ion intoxication, and more precisely its form resulting from the lack of access to water. The piglets were purchased in Denmark and they were transported to Poland within 24 hours, most probably with a limited or even non-existent access to water. However, the said breach of transportation regulations was not proved.

Unfortunately, we failed to obtain more detailed information with regard to transportation conditions, or the ingredients of the feed at the farm of origin. We may only presume that the direct cause of intoxication was the limited access to water during transportation. The situation could have also been influenced by the level of salt contained in the feed used at the farm which the animals originated from. This may be further confirmed by the symptoms and post-mortem lesions observed in the gastrointestinal tract of the diseased pigs.

Once unloaded at the destination farm, the pigs, which as a result of previous actions had a raised level of sodium in the body, were given unlimited access to fresh water, which triggered a sudden onset of clinical signs.