Sow mortality has increased considerably in the last few years. Today, mortality rates of 10% or more are considered normal. This last year in Spain we exceeded 15% mortality on average according to SIP Consultors data, which means that 50% of producers in Spain (at least those who share their data with SIP Consultors) exceeded this figure. What is happening in Spain is not unique from what is happening in other parts of the world. Combined data from farms in the USA, Canada, Australia, and the Philippines estimated a 13.56% sow mortality rate in 2021 (Eckberg, 2022) and naturally, this is cause for concern. Of all these losses, a significant percentage are culled sows and another percentage are sows that die suddenly. In general, the causes are rarely accurately diagnosed and, consequently, it is difficult to implement measures to reduce losses.

To reduce mortality, it is essential to diagnose the causes, and to do so we must be able to answer four basic questions:

- How are they dying?

- Who is dying?

- When are they dying?

- Where are they dying?

How are sows dying?

The first thing we need to look at is whether the high mortality is due to on-farm euthanasia of sows. Under current welfare regulations, it is possible that sows that cannot walk on their own or those that have very obvious lesions (uterine or rectal prolapses) cannot be sent to slaughter and must be euthanized on the farm. When we are dealing with the problem of euthanized sows, the diagnosis is somewhat simpler.

- If the sows are euthanized due to lameness, we know what problem they had, but not the cause of the lameness. Generally, lameness problems tend to be associated with young sows: first or second parity, as they are usually related to what happened during the rearing or acclimation phase. Diets that are not properly balanced in the rearing phase can produce very heavy sows with weak bone development that can lead to fractures (epiphysiolysis or apophysiolysis) or problems with joint cartilage in the extremities (osteochondrosis). Other times, the problem derives from infections suffered during the acclimation period (or post-transport to the destination farm): mycoplasmic arthritis or polyserositis processes could have consequences that compromise the reproductive viability of the affected females.

- If the sows are euthanized due to pelvic organ prolapse: uterine, vaginal, rectal, or urinary bladder, the diagnosis, again, is easy but knowing what the cause was to avoid these problems is more difficult. The presence of mycotoxins in the feed is perhaps the most common cause, but there may indeed be other causes, among which hypocalcemia, anemia in sows, poor body condition, constipation, misuse of prostaglandins, and excessive feed near farrowing have been described. Not to mention that a certain genetic predisposition has been observed.

Which sows are dying?

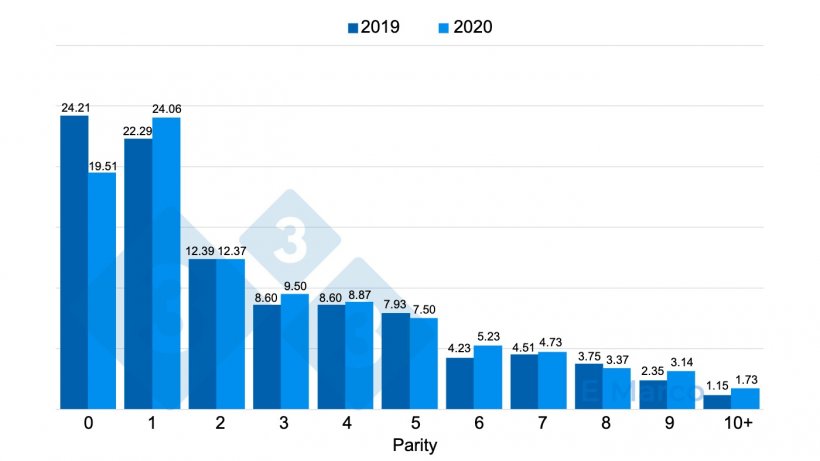

On farms where there are no mortality problems, mortality tends to increase with sow age or parity. In a study published in 2017, the risk of mortality increased by approximately 30% between the first and seventh parity, this percentage being slightly higher when looking at just the sows that died during the lactation phase. Older sows tend to present individual problems that can result in death: endometritis, cystitis-pyelonephritis, neoplasia, uterine prolapse, etc., and naturally, with every increasing parity the probability of suffering from problems increases.

On commercial farms, sows must produce in the presence of disease. Infections such as PRRS, PCV2, etc. are common on our farms. When mortality is concentrated in young sows, we should think about what problems may have affected them during the rearing phase or how the health acclimation has been carried out on the farm. These types of infections can leave chronic lesions due to secondary bacterial complications that could limit lung capacity (fibrinous pleuritis) or heart capacity (fibrinous pericarditis, vegetative endocarditis, etc.). When this is the problem, sows tend to die around farrowing, as this is when oxygen demand is greatest and lung and heart capacity are at their limit and can collapse if health is not optimal.

As we mentioned in the previous point, it is generally the young sows that are euthanized due to lameness problems.

In the next article we will address the following two basic questions that we should ask ourselves when faced with a sow mortality problem: "When do sows die?" and "Where on the farm do the deaths occur?"