This is the third installment of the saga that was first published in December 2012.

The first two articles discussed the need to seek the best weaning date to get the best services and the best possible care at farrowing. The production situation has changed a lot, due to improvements in health, facilities, management, nutrition and genetics. The most important change of all, which affects production the most, is the length of the sows' gestation (more than 115 days in modern genetics).

We currently come across sows that farrow many more piglets than before, piglets that we must be able to raise. We must not forget that besides piglets, sows have a high capacity to produce milk, capacity that must be taken full advantage of.

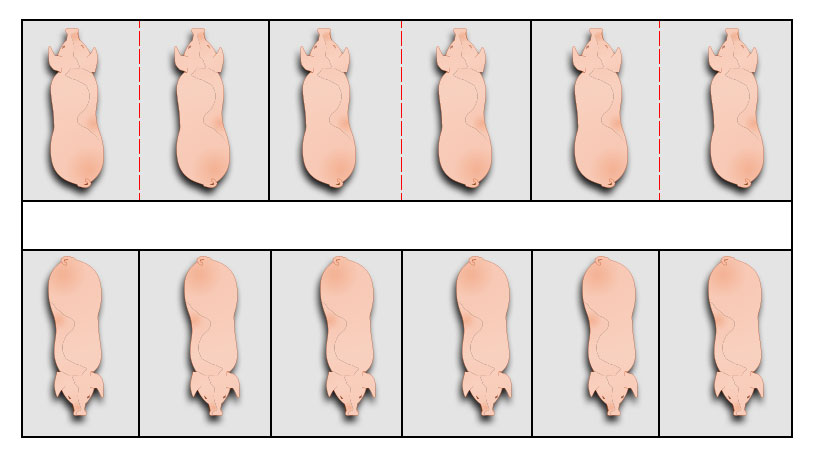

Figure 1. Today, there are sows that farrow many more piglets and more viable than before.

The need for milk is so great that different systems are being developed to provide artificial milk to piglets as an alternative.

Are these systems necessary? Are modern sows really capable to produce all the milk their piglets need?

Soaring prolificacies and increasingly better management have shown —in a practical way— that a sow with 14 teats can feed 16 piglets without problems.

What does "without problems" mean? Without the piglets becoming uneven, with good weaning weight, without differences with other piglets who have had "their" own teat for the duration of the lactation period.

We had always known that each piglet has its own teat, the first days of life a hierarchy being established between siblings that ends up with the allocation of the best teat for each piglet based on their capabilities.

We now know that this is only half true. This is true when there are more teats than piglets. But, if there are more piglets than teats, and they are all strong and viable, teats are shared.

This allows for the full use of the available milk. Teats are completely drained of milk, and this stimulates greater milk production.

Once we make sure teats are shared, the next step is to consider lifting partitions in the farrowing unit, thus allowing piglets of different litters to mix and socialize.

Figure 2. Farrowing room with partitions removed.

The first advantage is obvious: the animals make much better use of the lying area.

But, are there other advantages? Is milk really better used? Can the ceiling of milk production be reached?

In her end-of-degree project, Ara Yaiza proves it.

Piglets from 36 litters were individually weighed. Half of the piglets in each room were socialised in pairs by removing the barrier between both litters.

Every piglet was weighed at three timepoints:

- When processing the piglets (2-4 days old).

- At weaning.

- 4 weeks after weaning.

Piglets were socialised at an average age of 11 days.

The differences in weight between socialised and non-socialised piglets are significant (Table 1.)

Table 1. Mean least squares (± SE) of piglets' live weights depending on treatment (socialized / control).

| Socialised | Control | P | |

| Weight 1 (processed) | 2.14 (±0.03) | 1.93 (±0.03) | 0.01 |

| Weight 2 (weaning) | 7.41 (±0.1) | 7.11 (±0.1) | 0.03 |

| Weight 3 (4 weeks post-weaning) | 13.23 (±0.23) | 12 (±0.24) | 0.05 |

As proved when comparing weight coefficients of variation (Table 2), socialised piglets don't only grow bigger, but they are also more homogeneous.

Table 2. Weight coefficients of variation (%) in piglets from socialised and non-socialised litters.

| Socialised | Non- socialised | |

| Weight 1 (processed) | 23.66 | 25.02 |

| Weight 2 (weaning) | 19.32 | 20.86 |

| Weight 3 (4 weeks post-weaning) | 24.98 | 26.95 |

One of the doubts that arose at the time of the test was how to choose the right time to socialise litters. In the wild, socialisation usually starts at the age of 10 days. Table 3 shows that the results obtained after weaning are better when socialisation is delayed beyond 10 days of life.

Table 3. Means (± SE) of live weights depending on age at socialisation.T

| Start of Soc. ≤ 10 | Start of Soc. > 10 | P | |

| Weight 2 (weaning) | 7.23 (±0.08) | 7.39 (±0.13) | NS |

| Weight 3 (4 weeks post-weaning) | 14.38 (±0.08) | 15.23 (±0.21) | ≤0.001 |

Despite the limitations the study may have (sample size, baseline weights...) it seems clear that socializing in the farrowing unit is advantageous for piglets, both in the farrowing unit and at the beginning of the growing phase.

The door is already open, further research is needed to try and determine the optimal time for socialization, the number of litters involved, etc., thus making the most of such a precious asset as sow's milk is for our production systems.