Influenza virus transmission between humans and pigs is an ongoing challenge, as we do not fully understand all the factors that cause infections to become zoonotic, some even pandemic in scope. Nor do we fully understand how, where, and when infections from humans are transmitted to pigs. Transmission of viruses from people to pigs is more common than previously thought, and what happens is that when viruses of human origin mix with influenza viruses that are in pigs, these viruses can reassort and give rise to new infections that are a risk to people and pigs.

The key question is:

What can we do to prevent or at least minimize the risk of two-way transmission of the influenza virus?

We know that influenza can be transmitted by direct contact routes between infected animals and people and by indirect routes, either by contact with contaminated materials or through the air.

We recently completed two studies demonstrating the efficacy of basic interventions at the human-pig interface:

- Hand washing: we know the influenza virus can be easily transmitted via contaminated hands.

- Protecting the airways: we know the influenza virus is aerogenic and can be inhaled and penetrate the lungs and cause pneumonia.

Hand washing: essential but not enough

In the handwashing study, we tested four treatments:

|

|

|

|

|

| washing hands with just water | washing hands with soap and water | using an alcohol gel | using disposable gloves |

The study participants were first in contact with influenza-infected animals for 10 minutes and then their hands were tested for the presence of influenza virus before and after the treatments. We found that all the treatments contributed to reducing the presence of the virus on the hands but only the alcohol gel and the use of disposable gloves were sufficient to eliminate or, in the case of the gloves, avoid contamination of the hands in a significant way.

As expected, hand washing with water alone did little to reduce the load of influenza on the hands. However, hand washing with soap improved the situation somewhat, but not enough to remove all of the virus genetic material that was present on the hands. These results should not be interpreted to mean that hand washing with soap is not necessary or effective, but rather that this step should be supplemented with the use of an alcohol gel. Hand washing with soap has many other advantages in preventing the transmission of other diseases and should be upheld.

Our results reaffirm that, in addition to hand washing with soap and water, it is necessary to include hand treatments such as using alcohol gels and disposable gloves as part of biosecurity protocols.

Use of masks on the farm

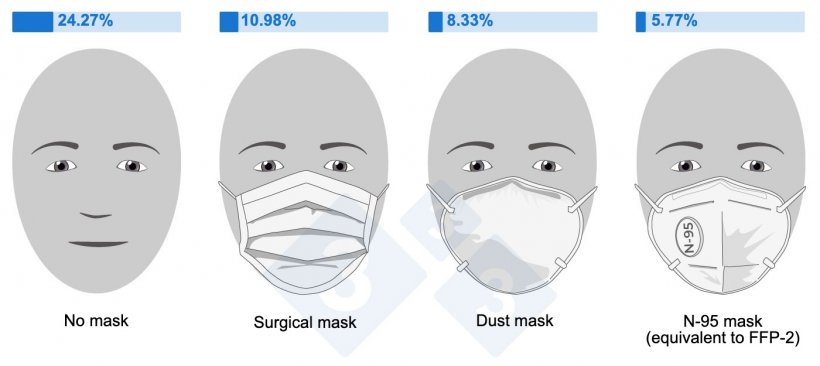

The other study we conducted evaluated the use of masks to prevent or mitigate influenza virus transmission via the airborne route. The use of masks on farms is bothersome and they are rarely used. In this case, we tested three types of masks and compared the results to not using masks.

- surgical mask

- dust mask

- N-95 mask (equivalent to FFP-2)

Farm employees tested the N-95 mask, a dust inhalation prevention mask, and the surgical mask typically worn by surgeons. We took nasal swabs before and after using the various masks from workers performing farm management tasks on pig farms with clinical influenza, and we analyzed them to see whether or not we found influenza virus genetic material. It is important to emphasize that the workers used the masks as they wished. We gave them general instructions on how to use them, but we did not oblige them to use them in the most effective way because we know that it is not easy to wear a mask all day on the farm. Many of the masks are not comfortable and are rather bothersome.

Our study proved what we already knew. Workers breathe in the influenza virus if it is in the air. We also showed that workers who did not wear masks had more virus in their nostrils than workers who wore masks. In other words, the use of masks helped workers protect themselves against the presence of the virus in the air. The percentage of positives was:

However, we did not see significant differences between the use of the different masks, although the N-95 had a numerical advantage. It was also interesting that workers preferred using the surgical mask since they considered it more comfortable. This study reminded us that it is important to take into account workers' preferences in order to maximize mask use, even if their preferred mask is not the theoretically most effective.

In summary, with these studies, we have seen that we have tools that we can employ to prevent bidirectional transmission of influenza virus between people and animals. These biosecurity tools are basic and must be implemented regularly and continuously if we really want to prevent virus transmission between people and animals. If biosecurity measures are both simple and incorporated into the farm routine, they are doubly beneficial.