The bacterial agents that cause pneumonia in pigs and are capable of causing lesions on their own can be classified as primary agents. These include Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Bordetella bonchiseptica, and some strains of Pasteurella multocida. Secondary agents are those that act following the prior infection of a primary agent or in immunocompromised animals; among them are found most of the P. multocide strains, Streptococcus suis, Glaesserella parasuis (formerly Haemophilus parasuis,) and Trueperella pyogenes.

Among the primary agents, M. hyopneumoniae, the causal agent of Enzootic Pneumonia

, takes on special importance for being a chronic process characterized by severe economic losses on pig farms- associated with decreased average daily gain, increased feed conversion rate, and increased mortality due to secondary infections. This prokaryote belonging to the Mollicutes class, is highly pleomorphic and is characterized by its lack of cell wall, its circular double-stranded DNA, a polysaccharide capsule with radial fibrils, and by being very difficult to culture.

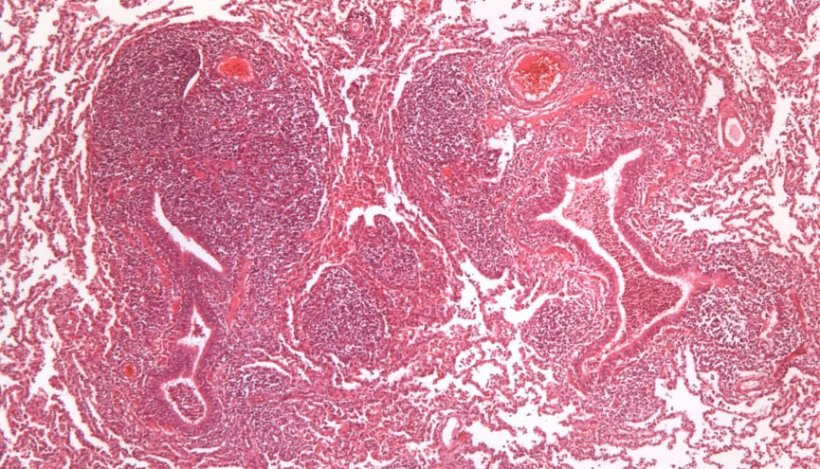

To carry out its pathogenic action it binds to the cilia of the respiratory epithelium cells causing a loss of cilia and altered mucociliary system function, which means that pulmonary secretions, inhaled particles, and pathogens entering the airway cannot be eliminated, so they progress toward the lower respiratory tract, complicating the respiratory process. At the pulmonary level, this agent causes bronchointerstitial pneumonia that is macroscopically characterized by the appearance of red areas of consolidation, well defined from the rest of the parenchyma, in the cranio-ventral portions of the lung (Figure 1). At a microscopic level, hyperplasia of peribronchial, peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphoid tissue is observed, which is very characteristic of this process (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Bronchointerstitial pneumonia caused by M. hyopneumoniae.

Figure 2: Peribronchiolar lymphoid tissue hyperplasia caused by M. hyopneumoniae.

A. pleuropneumoniae (App) is an encapsulated, gram-negative, coccobacillus bacterium with two biotypes: biotype I, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) dependent, and biotype II, NAD-independent. There are 18 serotypes: 1-12 and 15-18 belong to Biotype I, while serotypes 13 and 14 belong to Biotype II. App produces 4 toxins, Apx I, II and III, which are specific to certain strains, and Apx IV, which is common to all strains, which is why the latter toxin is the target on which several indirect ELISA diagnostic tests are based. This bacterium colonizes in the tonsils and from there it moves to the lower respiratory system, adhering to the alveolar pneumocytes, where it secretes toxins, which will have hemolytic and cytotoxic effects, altering the function of the endothelial cells; and the phagocytosis of the alveolar macrophages will lead to the activation of the coagulation cascade, microthrombus formation, and ischemic necrosis phenomena, which are responsible for the most characteristic lesion of this pathogen, the appearance of infarct areas in the lung.

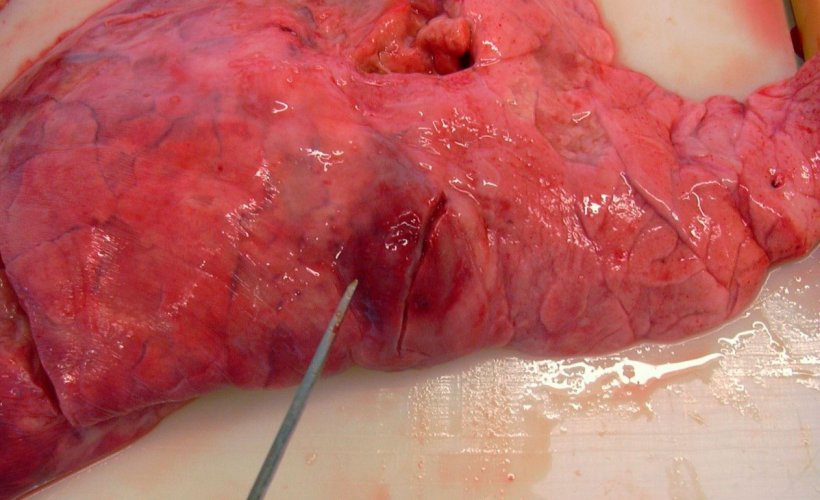

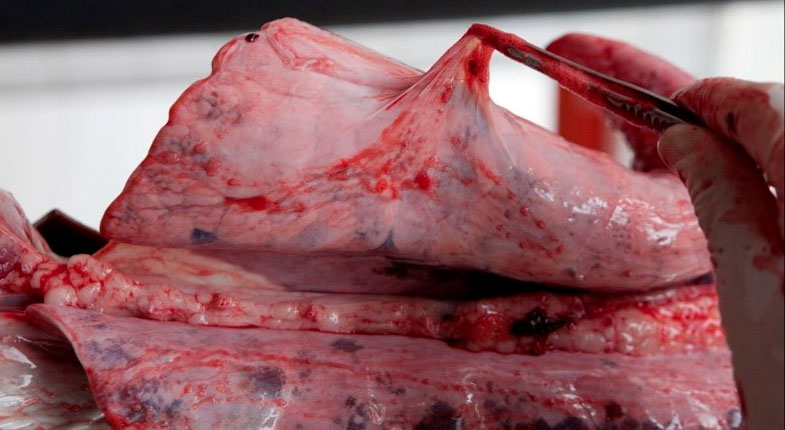

The lung lesion pattern it causes is fibrinous bronchopneumonia. In hyperacute and acute cases, the lesions are observed mainly in the dorsalcaudal portions of the lung (Figure 3), with areas of coagulation necrosis (infarction) and hemorrhage, that are friable and have a marble-like appearance when cut. Microscopically, the presence of fibrin and degenerated leukocytes can be seen in the lumen of the alveoli, bronchi and bronchioles, along with different-sized areas of necrosis and hemorrhages, and alveolar and interstitial edema, with the appearance of fibrinous pleuritis also being common. These same lesions can be produced by some very virulent strains of P. multocida, so to help us make an assertive diagnosis, we will need the clinical history, presentation of macroscopic lesions, and microbiological analysis.

A. pleuropneumoniae can also occur chronically, where hematogenous spread occurs from the acute lesions, and whitish-colored, multifocal lesions of variable size appear all over the lung.

Figure 3: Caudal lobe lesions produced by A. pleuropneumoniae

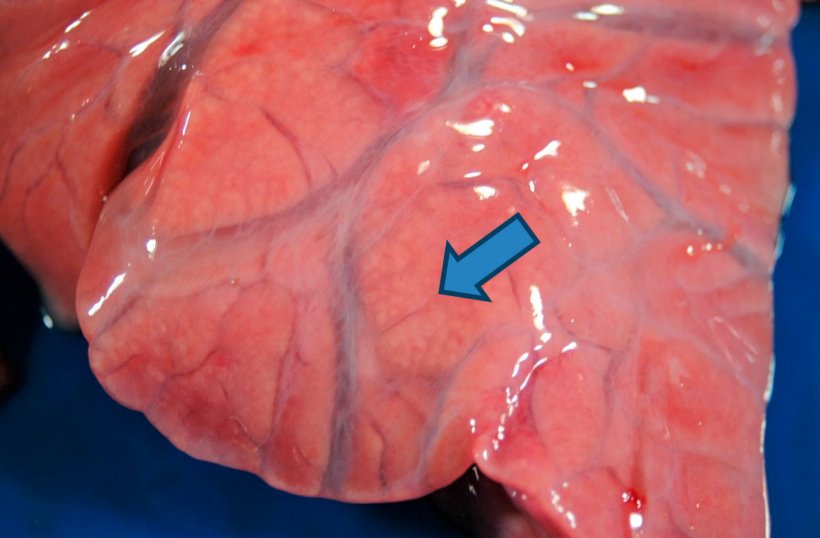

Most strains of P. multocida act as secondary agents and the type of lesion they cause can vary from fibrinous bronchopneumonia to catarrhal purulent bronchopneumonia. In the former, a fibrin exudate is produced in the alveolus accompanied by the deposit of fibrin on the surface of the pleura. In addition, pockets of coagulation necrosis occur in the lung as a result of thrombosis in the blood vessels. In catarrhal purulent bronchopneumonia, a mucous exudate or catarrhal-purulent appears in the airways (trachea, bronchi and bronchioles) and in the lumen of the alveoli (Figure 4). Another agent causing this type of bronchopneumonia, especially in the first weeks of life, is B. bronchiseptica, which may also be accompanied by a process of non-progressive atrophic rhinitis.

Figure 4: Purulent bronchopneumonia: enlargement of the cranio-ventral consolidation where small yellowish-white areas (arrow) are observed corresponding to the pulmonary alveoli filled with purulent material. Interstitial edema is also observed.

Bacterial agents such as T. pyogenes and S. suis can be related to embolic pneumonia processes, associated with processes of omphalophlebitis, bacterial infections of the skin or of the hooves (T. pyogenes) or related to cases of endocarditis muralis (S. suis), situations in which the bacteria reach the lung via hematogenous routes from these lesions. Macroscopically, multi-focal lesions are observed distributed throughout the lung, whitish in color and ranging in size from 1 mm to 2 cm in diameter, surrounded by a reddish halo in the most acute cases, and rapidly evolving towards the formation of abscesses (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Embolic pneumonia caused by T. pyogenes.

Three main bacteria stand out in the cases in which fibrinous pleuritis deposits are observed on other serous surfaces in addition to the pleura: G. parasuis, M. hyorhinis and/or S. suis. These lesions often can go clinically unnoticed, and the slaughterhouse is where we can observe increases in pleural adhesion due to the these processes becoming chronic. (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Slaughterhouse finding: fibrous pleuritis.

Although most of the bacteria that affect the respiratory system are opportunistic agents, we must always keep in mind the two primary bacterial agents that are considered among the most pathogenic in pigs: M. hyopneumoniae and A. pleuropneumoniae.