The challenge: predicting the unpredictable

One of the many challenges associated with tail biting behaviour is that outbreaks appear to be unpredictable, often starting without any apparent cause. Tail docking of piglets before seven days of age is one method widely used to reduce the risk of tail biting later in life, however this practice should be thought of as a last resort after other risk factors for tail biting have been improved, such as providing enough space and enrichment. Tail docking is an undesirable mutilation; it is known to be painful for piglets and does not completely eliminate tail biting. Routine tail docking has not been permitted in the EU for over 25 years, with the original directive on pig welfare (Directive 91/630/EEC) amended in 1994 to include this regulation and subsequent updates reinterating that there should be no routine docking (Council Directive 2008/120/EC). Despite these regulations over 70% of pigs in the EU are tail docked. Farmers are reluctant to risk leaving tails intact, partly because of the unpredictable nature of a tail biting outbreak. However recent research shows that there are behavioural changes in pigs before a damaging tail biting outbreak starts.

What are the early warning signs of tail biting?

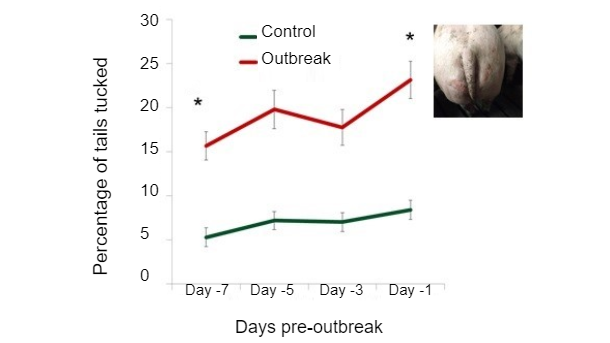

There have been various studies examining the behaviour of pigs in the lead up to a tail biting outbreak. Increased activity, increased object and tail-directed behaviours and lowered tail posture are all behavioural signs observed before an outbreak. Our research at SRUC focussed on changes in tail posture as a promising indicator to investigate further. We video recorded grower pigs 24h a day throughout the weaner-grower period to continuously observe changes in their tail posture. 23 different groups (approximately 27 pigs per group) were raised with intact tails under intensive conditions. There were 15 groups where tail biting outbreaks occurred, and 8 with no outbreaks. Outbreak groups had altered tail posture, with fewer curled tails and more lowered and tucked tails compared to non-outbreak (control) groups. There were significant changes in tail posture in the week before an outbreak with outbreak groups changing from 15% tucked tails seven days pre-outbreak to 20-25% tucked tails one day pre-outbreak. This showed that tail posture has the potential to be used as an early warning indicator of a tail biting outbreak, but how easy is it to observe on farm?

Globally pig farming, like other livestock sectors, has become more integrated with an increasing number of very large farms operating without a parallel increase in farm staff. This means the ratio of stockpeople to animals is not necessarily in the animal’s favour when it comes to individual monitoring. A survey of medium to large sized pig farms in the Netherlands, showed that pig farmers with very large farms spend (on average) 5 seconds per day per finisher pig on inspection, with the largest farm surveyed (10,000 pigs) only averaging <1 second per day (HAS University). So the magnitude of changes seen in tail posture in outbreak groups might not be that easy for staff to detect during such brief inspections. Continuously monitoring animals using Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) tools is one approach we looked at to automatically detect altered tail posture.

Automating detection of behaviour

PLF uses various sensor technologies capturing data from animals, groups of animals or buildings. Algorithms then translate that information into something meaningful for the farmer (e.g. key performance, health or welfare indicators). By continuously capturing information about individuals or groups, the algorithms can detect when changes from normal behaviour occur. Identifying these changes earlier than typical by-eye inspection is key to such technology being useful to the farmer. In the case of tail-biting the earlier a potential outbreak could be predicted, the easier it would be for the farmer to stop the outbreak from ever occurring.

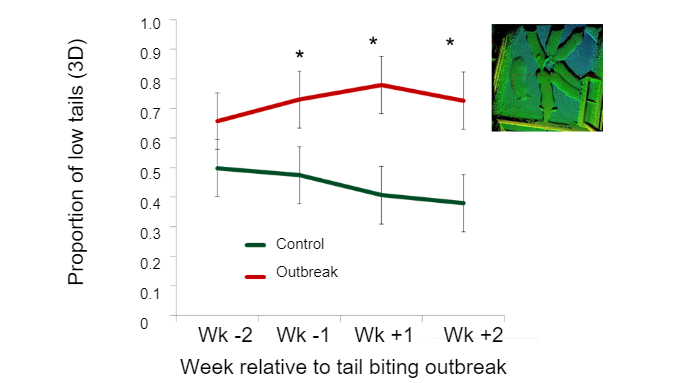

For our project we used 3D cameras (using time-of-flight technology) to automatically measure whether pig tails were up and curly, or held down. This technology was already being used to measure pig weight and our industry partners adapted the algorithms to detect tails. The proof of concept work on one of our research farms demonstrated that 3D data from groups of pigs with tail-biting outbreaks showed the proportion of low tail detections increased pre-outbreak and declined post-outbreak.

Trusting the tech

We wanted to further validate the technology so we checked 926 cases of 3D tail postures by eye against 2D video recordings. The algorithms could detect tucked tails with a 74% accuracy. We concluded that 3D camera technology can automatically detect differences in tail posture. We are further optimising these algorithms to test the technology on a range of farm types and tail lengths and developing an automated detection system that can alert farmers of an imminent outbreak (the TailTech project).

The Impacts

Reliable behavioural indications of when an outbreak is imminent would provide farmers with tools for mitigating the outbreak at key time points (e.g. providing additional enrichment), thus preventing pain and stress from being bitten. The project also aims to reduce the need for tail docking thus addressing welfare and ethical concerns. Fewer bitten pigs reduces the risk of carcass condemnation at the abattoir as well as reduced veterinary and labour costs on farm. Tail injuries and subsequent secondary infections are treated on farm using antibiotics, and a reduction in this issue would help address the growing concern over anti-microbial resistance in human healthcare.