A new revolution is about to reach the pig sector; its implementation will probably happen earlier than we thought for, amongst others, a very simple reason: it is something that comes from other aspects of life cattle and pig production are not, in general, unfamiliar with. We are talking about new information management.

This development is based on the following four concepts, that interact redefining many aspects of our business:

- Connectivity-mobility

- The Cloud

- Big Data or massive data

- Business intelligence systems as new analysis tools

Why are all these concepts —that seem alien to our area of activity— destined to mark the evolution of our industry in the coming years? Because they are mature, inexpensive and simple enough to be introduced in our sector; and the first producers to do this will almost invariably be the ones with a business mindset (not necessarily related to size, but to attitude).

So far, when it comes to data management, we almost unconsciously think of animal data, specifically sows. This is basically what the concept means, but we can probably also add economic data, albeit always from a personal and internal approach (in other words, not generally —as opposed to reproductive data—, collected or analyzed or shared beyond the scope of the company itself). This is going to change soon, for two reasons:

- We need to work more thoroughly and accurately in other animal-related data areas, including but not limited to health monitoring, biosecurity control, antibiotics or feed use.

- Machines and devices that generate continuous data without human intervention are becoming available.

As per the first point, the amount and frequency of managed data is going to increase dramatically for technical reasons, as well as internal quality control, company's strategic decisions and regulatory reasons. This will require a considerable effort from the staff in charge of this task, and different systems will be used for this purpose: from the classic capture in paper for further processing, digital pens and PDA's to web apps on mobile phones or tablets; all of them can be valid depending on their purpose and the user.

But perhaps the most profound change will come from systems capable of generating data continuously without human intervention (what has come to be known as 'the internet of things'), including:

- Electronic feeding systems for pregnant sows where each sow is identified thanks to a chip implanted under their skin

- Lactating sows feeders, coupled to the feed drop

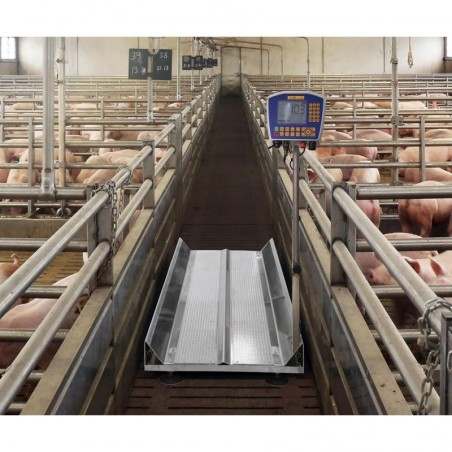

- Electronic devices for animal weighing and feeding control in fattening pigs

- Sensors for temperature, relative humidity, CO2, water consumption and electricity consumption

- Remote weighing devices using 3D technology

- Automatic semen quality analyzers integrated on iPads

All these devices are already on the market —some of them have been for a few years—, and generate huge, typically underused amounts of data; for example, the electronic feeding machines for pregnant sows are generally not used for much more than to see if a sow has eaten what it should or not.

In this situation, producers and technicians have to decide, in relation to point 1, whether or not to generate data and, in relation to point 2, whether or not to use the already generated data (automatically captured). The most likely answer to both questions will be 'yes' (YES, they will be generated, and Yes, they will be used). So, you'd better start thinking about how to deal with this scenario with the highest efficiency and lowest cost.

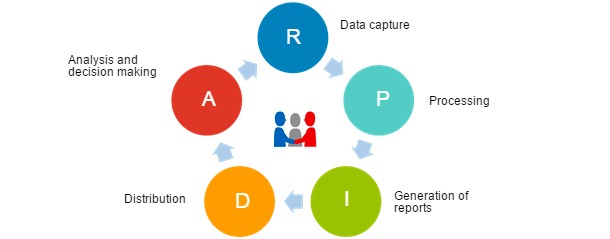

In order to develop proper data management and productivity analysis, any professional pork producer (we could almost say any company) should address the following diagram (Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Optimization cycle for data management.

This scheme is generally not optimized (significant gaps are found not only in family farms or medium-size cooperatives, but also in many large companies.) Thus, the following are very common:

- Data are not captured properly (or they are not the right data or the recording frequency is not appropriate)

- They are not adequately processed (due to lack of the necessary software tools —pig software packages optimized for every situation—, or lack of knowledge or time)

- They do not generate the expected reports by type, pattern or frequency (they are often produced late or in the wrong format)

- They are not correctly distributed (the report has to reach the right person, in the right way and at the right time; for instance, a list of underproductive sows to be culled that reaches the worker when they have already been serviced is completely useless)

- They are not understood, and decisions are made that the report wasn't calling for; it usually happens due to lack of time and training. The information is there, but the person responsible for making the decisions is not internalizing it. Therefore, decisions are not made or they are the wrong ones. This situation is very common because companies currently lack the position of "leading analyst", who would be the person responsible for understanding the production reports and implementing the necessary measures. In other words, in the absence of an "analyst" everyone figures out how to do their job as best they can.

The first analysis of this huge mass of data (automatically generated) reveal information of great interest, so far unknown. This happens with classic reproductive data (by the meticulous analysis of half a million services, we were able, at PigCHAMP, to predict the sow's performance for its entire life based on the results of its first farrowing —Lida Pineiro and Koketsu, 2015), and it looks set to continue with the data generated by the different machines. When they are properly processed and analysed, they show their full hidden value (information). This information value is much greater when we cross-reference data from different sources, such as reproductive data with feeding data. Our first results (not yet published), show some very important effects not described to date, which we will present in future articles.