One of the current challenges facing the swine production industry is to develop alternative housing systems rather than farrowing crates, which, since their introduction in the middle of the 20th century, have become the most widely used housing system worldwide. However, social pressure to eliminate crates in production has increased. In Europe, the legislative initiative "End of the Cage Age" that launched in 2018 managed to collect more than 1.5 million signatures, which forced the European parliament to present a proposal for legislative changes starting in 2027 (EC, 2021). This situation had already been preceded by EFSA's scientific opinion on the possible adverse effects of farrowing crates on sow welfare, as well as by the industry's technological developments of alternative systems. It is clear, therefore, that this context indicates that changes are coming in the medium-term, and the industry must be prepared to respond to these challenges. For example, countries such as Germany have declared that the use of permanent crates will be banned by 2035 and that only partial confinement for 5 days after farrowing will be allowed, in housing of at least 6.5 m2.

Crates were designed primarily to prevent piglet crushing and neonatal mortality, as well as to facilitate some management interventions with the sow. Neonatal mortality has been associated primarily with causes such as crushing, hypothermia, starvation/malnutrition, or combinations thereof (Edwards, 2002). Additionally, in today's context, the use of hyperprolific genetics has led to lower average piglet birth weights and increased mortality (Kobek-Kjeldager et al., 2020). The risk factors that cause the death of a piglet are associated both with its vitality at birth and during the hours immediately after birth (associated mainly with birth weight, hypothermia, and ability to intake colostrum), as well as with the maternal behavior and stress of the sow.

Prior to farrowing, the sow is subject to hormonal changes mainly associated with prolactin and oxytocin levels, which induce her to exhibit nesting behavior patterns (searching for and transporting material, rooting, digging). As shown in this video from the freefarrowing.org website, domestication, type of housing, or the presence of appropriate materials to perform the behavior, do not prevent the sow from displaying some of the characteristic patterns of nesting behavior.

The sow's inability to exhibit adequate nesting behavior in crates due to lack of both space and available materials has been associated with increased stress hormones such as cortisol, which act negatively on oxytocin levels. Hence, the connection between pre-farrowing and farrowing stress in the sow with reduced piglet vitality, since the duration of farrowing and the birth interval between piglets are increased as a consequence of stress, and colostrum and milk ejection may be delayed. It has been described that piglets born with low vitality, as a result of possible hypoxia during farrowing or low birth weight, may be at increased risk of remaining close to the sow to compensate for these deficiencies. Having lower vitality piglets is especially significant in litters with a high number of piglets since the social competition for a functional teat is very high. In this regard, one of the great challenges with using hyperprolific breeds, with an average of around 17.5 piglets born alive, is to achieve proper growth when the sow has only 14-15 functional teats. This challenge is especially important in housing systems without confinement. A recent study with hyperprolific sows reported higher mortality in standardized litters on day 1 with 17 piglets compared to 14 piglets/sow, and a relative mortality risk of 1.8 in non-confinement housing systems compared to crates (control group, relative risk of 1). In contrast, in the non-confinement housing systems, there was less effect of high udder competition in these large litters, with sows showing fewer udder lesions and piglets having a lesser tendency to estimulate the udder between feedings.

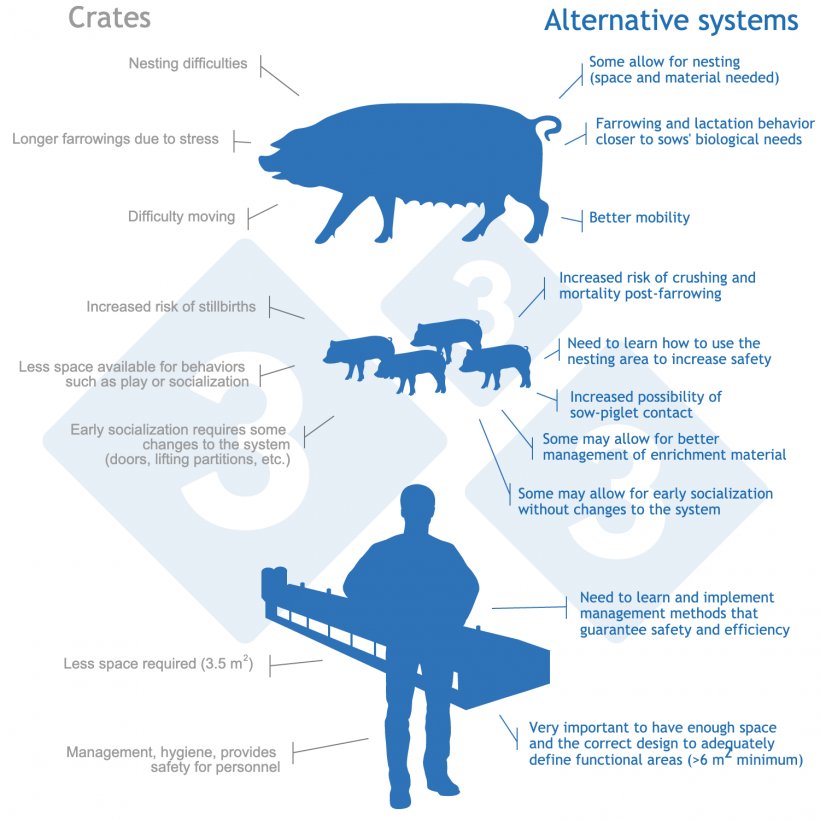

Alternative housing systems have good potential to improve aspects of sow welfare in the farrowing stage. However, proper design and management of these systems is crucial so that the positive effects on reducing sow stress are not outweighed by adverse effects on piglet mortality or on the ease of management and labor for farmers. A recent study has suggested that crates have a 22% higher relative risk of producing stillbirths compared to non-confinement or semi-confinement housing (Glencores et al., 2019). In contrast, cages still decreased the risk of neonatal mortality after weaning (14% higher in free-range systems), according to this meta-analysis. Furthermore, there are other aspects of management and space requirements in order to adequately define functional zones in new housing that still represent a challenge for development. In the infographic, crates and alternative systems have been compared according to their effect on the sow, the piglet, and the farmer. In the next article, we will describe the different types of alternative systems, namely those without confinement, those with temporary confinement, and group systems.