Article

Further assessment of fomites and personnel as vehicles for the mechanical transport and transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Pitkin A, Deen J, Dee S. Can J Vet Res. 2009 October; 73(4): 298–302

Article brief

What are they studying?

Successful elimination of PRRSv has been confirmed in individual farms, although re-infection due to indirect spread of the virus has also been reported. Routes of transmission include farm personnel and fomites (contaminated needles, boots, and coveralls).

The purpose of this study was to re-evaluate the role of fomites and personnel in the transport and transmission of PRRSV between swine populations by using large groups of PRRSV positive pigs housed in commercial facilities.

How is it done?

340 pigs were used for the study: The barn that was used as source of the virus housed 300 pigs (Facility B, where 100 pigs were inoculated intranasally with PRRSv), while the other 40 pigs were kept as a negative exposure population (A, n=20) and a positive exposure population (C, n=20).

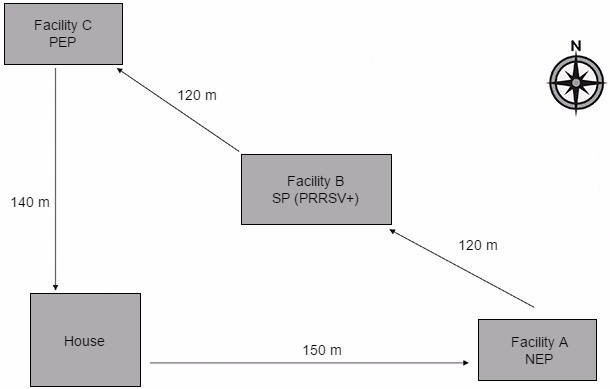

Figure 1. Diagram showing location of study facilities and direction of daily personnel movement between facilities. The arrows indicate the direction the personnel would travel on a daily basis during the study period. The purpose of each facility was as follows:

House: Point of study site entry which included a shower-in protocol at the start of each day.

Facility A NEP (Negative exposure population): The site used to validate the lack of PRRSV transport and transmission by fomites and personnel in the absence of contact with virus prior to entry.

Facility B SP (Source population): The PRRSV-positive site which was used to enhance exposure of fomites and personnel to infectious virus prior to entering facility C.

Facility C PEP (Positive exposure population): A site used to determine whether transport and transmission of PRRSV to naïve pig populations occurred following contact of animals in this facility with contaminated fomites and personnel.

3 people participated in the study: they took a shower, wore specific clothing and footwear, and walked from facility A to facility B with infected pigs and then to facility C. When entering barns A and B, personnel wore specific coveralls and boots, washed hands and carried out normal operations common to commercial swine farms (checking feeders, drinkers, inspecting and treating animals, etc.).

After the daily inspection in facility B, personnel walked to facility C and entered the pens without removing the boots or coveralls used in facility B or washing their hands. Feed bags, blood- testing equipment, and cable snares were also taken directly from facility B into facility C, without previous sanitation.

The 2-week experiment was replicated 7 times. On days 2, 5, 7, 9, and 12 of each replicate, blood samples were collected from the pigs in the negative exposure population and the positive exposure population.

Swabs samples from personnel hands, boots and coveralls were also taken, and air samples and insects collected and tested for the presence of PRRSV RNA.

What are the results?

There was no transmission of PRRSV via any route to facility A (all swabs and air samples turned negative) in any of the 7 replicates, and all blood samples collected (n = 700) were negative.

On the other hand, transport of PRRSV to facility C was confirmed in all 7 replicates since the virus RNA was detected on coveralls, boots and fomites. Also, transmission of PRRSV to the positive exposure population in facility C was observed in all 7 replicates, PRRSV RNA being detected in the serum of at least 1 pig in each replicate. This infection was confirmed within 5–7 d in all 7 replicates.

PRRSV was not observed in facility C following a change of clothing and footwear after showering, despite prior contact with the facility B source population.

What implications does this paper have?

People and fomites are a risk factor for new PRRSv infections. Producers and veterinarians should regularly audit the movements between facilities and the sanitation procedures of incoming people, materials and equipment.

Appropriate sanitation measures implementation, as well as reinforcing their importance, is key to reduce the risk of PRRSV entry via these routes.

|

Our previous article explained how easily transport vehicles could be involved in the introduction of new strains of PRRS virus on farms. This one explores the possibility that workers or materials used on the farm may spread the virus, showing that the probability of infecting healthy animals during a visit is very high when infected animals have been visited previously and no clothes-and-boots-changing protocol has been followed; or when the same material is used in both farms. The health status of the farm is commonly used to determine the biosecurity measures that are going to be implemented. This is one of the reasons why mandatory showers before entering the farm is still a measure only found in a small percentage of farms. However, the obligation to wear the farm own clothes or disposable coveralls, and to change shoes or use plastic shoe covers are very common. Surely these measures are effective, but then we make some mistakes that ruin all the work done. How many farmers require their maintenance staff to wear clothes or shoes other than their own? How many make them disinfect their tools or protect them from contact with surfaces? How many farms require hand washing or using gloves? Biosecurity measures for visitors should be implemented in all farms without exception, and hand washing with soap and subsequent disinfection should be compulsory in those farms where showering is not. The paper conclusions are not only important to prevent new outbreaks; they should also be taken into account for internal management. There are not few farms that keep the PRRS virus recirculating at some point in their work flow. When these recirculations happen at an advanced age —end of weaning or the start of growing periods—, they are, in many cases, the consequence of side infections caused by previous batches where the virus was present, and not the result of the production of viraemic piglets. The implementation of some of the measures described in the article between batches would allow, in many cases, to break the infection cycle and obtain negative results. These measures would be as simple as providing footwear, specific coveralls (it could be a disposable coverall to wear over normal clothing), batch-specific materials and hand washing before coming into contact with a new batch. |