Everyone knows atrophic rhinitis (AR) as a disease characterized by deformation. of the snout. This deformation results from an irreversible contraction (atrophy) of the nasal turbinates, caused by toxins produced by two bacteria: Pasteurella multocida type D and Bordetella bronchiseptica.

B. bronchiseptica, the bacterium

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a widespread bacterium on our swine farms. Its toxicity is due to the inflammation of the mucosal lining of the nose and lungs that generates but often it produces also mild lesions in the form of a temporary atrophy of the nasal turbinates. This means infection due to B. bronchiseptica is often overlooked because the lesions are transient and reversible. An experimental study in which four-day-old piglets were infected with the bacterium, showed by CT scan of the snout, that the most severe atrophy of the turbinates occurs around six weeks of age, after which, the turbinates return to their original structure and no lesions are observed at the slaughterhouse. Since the diagnosis of atrophic rhinitis is often made by cutting the snout at the slaughterhouse, the non-progressive form of atrophic rhinitis can be overlooked.again.

The impact of B. bronchiseptica goes beyond macroscopic lesions as slso the cilia in the trachea are affected. These cilia are responsible for removing the foreign substances and germs from the body and carry them into the throat so they do not reach the deeper respiratory system. Thus, infection with B. bronchiseptica makes animals more susceptible to other pathogens.

The best-known example is infection by Pasteurella multocida type D, a bacterium that by itself does not possess the ability to colonize the respiratory tract but previous colonization by B.bronchiseptica facilitates subsequent colonization by Pasteurella multocida type D.

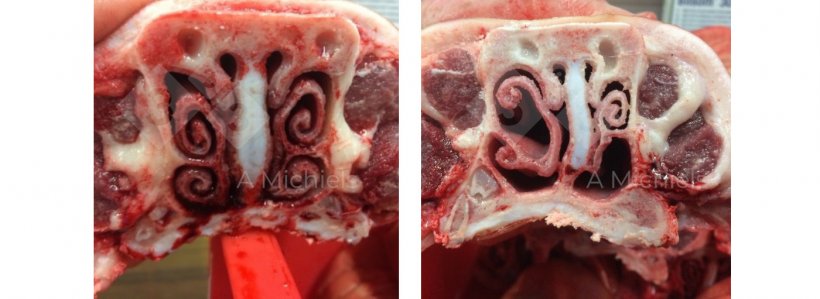

Figure 1. Left: A pig with healthy turbinates where the nose is the first filter to combat the entry of respiratory pathogens. Right: turbinates affected by non-progressive atrophic rhinitis. The snout twists, shrinks and wrinkles. Piglets show sometimes even nasal bleeding.

Bordetella bronchiseptica as a predisposing factor: beyond co-infection with Pasteurella

B. bronchiseptica will act as an opportunistic pathogen, contributing to porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC). Due to its pathogenesis, it produces a temporary atrophy of the nasal turbinates and affects the respiratory cilia of piglets during the nursery phase, facilitating the entry into the organism: of pathogens such as the following:

- Gläesserella parasuis (cause of Glässer disease)

- Streptococcus suis

- PRRS virus

- Influenza virus

Therefore, protection against B. bronchiseptica can reduce the risk of various respiratory infections and help animals fight them better.

B. bronchiseptica and its influence on Streptococcus

Microorganisms that cause primary respiratory problems are not the only ones that benefit from the path cleared by B. bronchiseptica. Streptococcus suis (S. suis) also has a free path when B. bronchiseptica has done its job destroying the turbinates, the first barrier to entering the respiratory system.

In an effort to reduce antibiotic use, legislation and production companies have put various measures in place to limit their use. Unfortunately, this also means limiting one of the tools that can be used to prevent Streptococcus problems on the farm. Therefore, in addition to improving piglet quality at weaning, biosecurity, and management, we must look for alternative methods to prevent Streptococcus infection. Vaccinating against B. bronchiseptica helps reduce S. suis-associated mortality by reducing the likelihood of S. suis gaining access to the piglet.

Case study

On a commercial farm in Europe, with a high mortality rate due to meningitis and arthritis, S. suis was isolated several times from meninges and joints. To control the clinical signs, the farm maintained routine medication with amoxicillin in the water. B. bronchiseptica was present in oral fluids but P. multocida toxin was not found. Since previous reports point to the control of secondary infections via the control of B. bronchiseptica, it was decided to investigate the influence of vaccination against non-progressive atrophic rhinitis in the prevention of S. suis infection. For this purpose, the following piglet groups were followed in parallel over time:

- Three batches from sows vaccinated with a vaccine against non-progressive atrophic rhinitis

- Three batches from non-vaccinated sows (control group)

Routine use of amoxicillin in water was discontinued during the trial.

Results

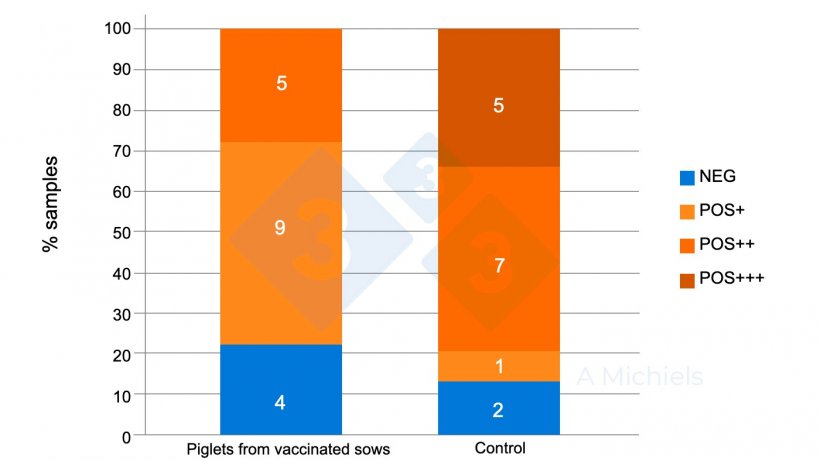

A clear reduction in the presence of B. bronchiseptica in the oral fluids of piglets at 5 and 8 weeks of age was observed in piglets from vaccinated sows (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Oral fluid samples from 5- and 8-week-old piglets. Piglets from vaccinated dams (left) show a strong reduction in the prevalence of B. bronchiseptica compared to results from the unvaccinated control group (right).

This reduction in the presence of B. bronchiseptica in oral fluids correlates with a 79% reduction in mortality due to meningitis in piglets in the vaccinated group. In addition, the total number of antibiotic treatments per 100 piglets was lower in the vaccinated group compared to the non-vaccinated group.

Table 1. Piglets from vaccinated sows vs. piglets from unvaccinated sows. Parameters with an (*) were significantly different within a column.

| Group | Weaned piglets | Nursery mortality (%) | Antibiotic use for every 100 animals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Meningitis | Diarrhea | Meningitis | ||

| Vaccinated | 3,209 | 2.13 | 0.07* | 18.78* | 0.25 |

| Not vaccinated | 2,820 | 2.49 | 0.34 | 25.49 | 0.47 |

This farm reduced the incidence of S. suis-associated mortality by vaccinating against non-progressive atrophic rhinitis. It is important, therefore, to determine if B. bronchiseptica is present on the farm, as lesions caused by this bacterium often go unnoticed.