Trace minerals are required for the normal development and functioning of the body. They are essential for the metabolic, endocrine and physiological control of growth, reproduction and immunity. However, compared with the requirements for energy and amino acids, those for minerals are not as well defined despite their importance to overall herd health and productivity. Their requirements are hard to establish and most estimates are based on the minimum required to overcome a deficiency and not necessarily to optimise productivity, or indeed to enhance immunity. Most of the studies to establish mineral requirements - and trace nutrients in particular - have been carried out pre 1990 and may not be relevant to modern sow genotypes with their considerably higher productivity.

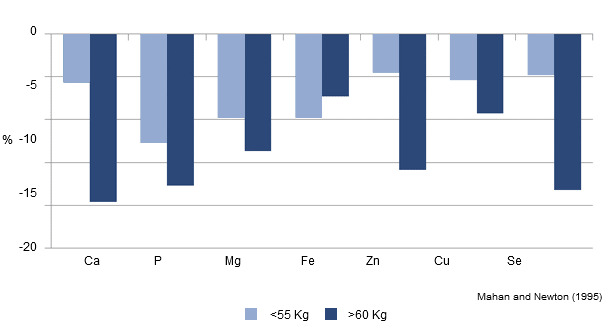

For example, Newton and Mahan (1995) showed that there was considerable depletion of minerals from the bodies of sows after weaning their third litter of piglets, compared with non-bred animals of similar age who were fed the same dietary levels of inorganic minerals (Figure 1). This suggests that the inclusion of inorganic minerals in the diet of modern hyperprolific sows may not meet their needs; hence the interest in organic minerals. These are proteinated or chelated minerals in which the trace mineral is chemically bound to a single or a mixture of amino acids or small peptides. In this form the minerals are more available and bio-active resulting in a metabolic and productive advantage. It is only possible to chelate transitional elements; other minerals, such as selenium and chromium that cannot be chelated are incorporated into yeast to provide the same benefits.

Figure 1. Sow Mineral Content: % change

The superiority of organic minerals for sows, when compared with the same levels of inorganic minerals, is shown in Table 1. The inclusion of organic forms of selenium and iron significantly increased their concentration in colostrum, milk and blood, as well as in the total body content of newborn and weaned piglets. This improved the metabolic, physiological and oxidative status of the piglets, resulting in better performance and overall health.

Table 1. Comparison of organic and inorganic minerals in pigs

| Inorganic | Organic | % Increase | Source | |

| Newborn piglet | ||||

| Liver Fe (mg/kg) | 219 | 278 | 27 | Egeli et al. (1998) |

| Liver Fe (mg/kg) | 1779 | 2171 | 22 | Bertechini et al. (2012)* |

| Blood Hb (g/dL) | 9.16 | 11.16 | 22 | Bertechini et al. (2012)* |

| Blood Fe (mcg/dL) | 174 | 228 | 31 | Bertechini et al. (2012)* |

| Blood Se (mg/L) | 0.060 | 0.092 | 53 | Svoboda et al. (2008) |

| Blood Se (mg/g) | 0.140 | 0.159 | 14 | Quesnel et al. (2008) |

| Loin Se (mg/kg) | 0.116 | 0.200 | 72 | Mahan (1994) |

| Colostrum | ||||

| Colostrum Se (mg/L) | 0.093 | 0.188 | 202 | Mahan (2000) |

| Colostrum Se (mg/L) | 0.095 | 0.168 | 77 | Peters & Mahan (2004) |

| Colostrum Se (mg/L) | 0.242 | 0.323 | 33 | Quesnel et al. (2008) |

| Colostrum Se (mg/L) | 0.205 | 0.270 | 32 | Yoon & McMillar (2006) |

| Milk | ||||

| Milk Se (mg/L) | 0.036 | 0.105 | 292 | Mahan (2000) |

| Milk Se (mg/L) | 0.056 | 0.101 | 80 | Peters & Mahan (2004) |

| Milk Se (mg/L) | 0.042 | 0.087 | 107 | Quesnel et al. (2008) |

| Milk Se (mg/L) | 0.060 | 0.098 | 63 | Yoon & McMillar (2006) |

| Milk Fe (mg/L) | 773 | 1014 | 31 | Bertechini et al. (2012)* |

(*) Values at 2kg/T inclusion rate

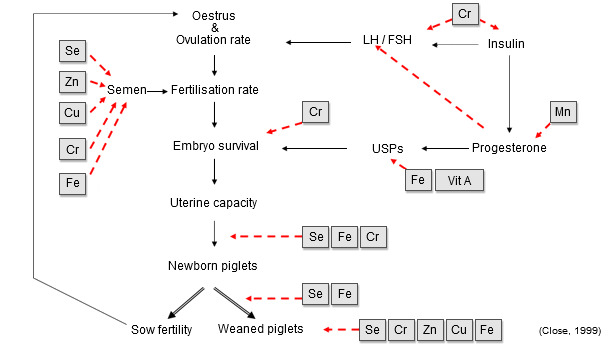

Different trace minerals impact at different periods of the reproductive life of the sow (Figure 2) and it is likely that the greatest improvement in sow productivity will be from a combination of minerals.

Figure 2. Components of Sow Productivity. Role of trace elements

In this respect Peters and Mahan (2008) reported that sows fed a combination of trace minerals in organic form produced more piglets per litter (p<0.05) compared with sows fed the same levels of inorganic minerals: 12.2 vs. 11.3 total born and 11.3 vs. 10.6 born alive, respectively. Performance was highest when the diets were supplemented with organic minerals at industry compared with NRC levels. They concluded that feeding sows organic trace minerals improved sow reproductive performance.

Similarly, Bertechini et al. (2012) showed that the total replacement of inorganic with organic trace minerals resulted in 1.1 and 1.0 extra piglets born alive when organic minerals replaced inorganic minerals at 1 and 2 kg inclusion rate, respectively. The weight gain of the piglets during suckling was also higher by 1.32 and 0.76 kg, respectively. Papadopoulos et al. (2009), on the other hand, concluded that partial substitution of inorganic minerals with a chelated mineral source during late gestation and lactation failed to exert significant effects on performance and total body mineral concentration.

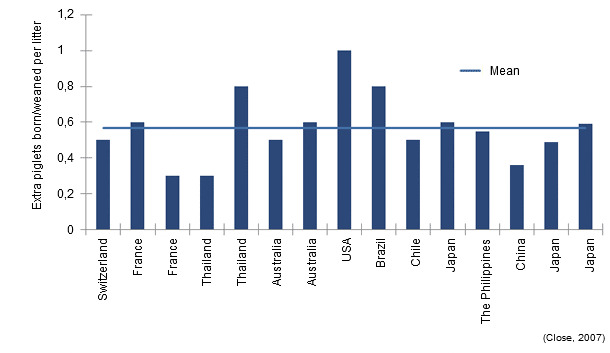

In a series of commercial trials, Close (2007) reported that the supplementation of the diet of sows throughout gestation and lactation with organic minerals increased the number of piglets weaned by 0.52 ±0.11 (n=15) with the response varying between 0.3 and 1.0 extra piglets per litter (Figure 3). The partial inclusion of organic minerals has also been shown to reduce claw lesions and lameness in sows (Anil et al, 2009), as well as increase the number of piglets born alive (11.07 vs. 10.44), and litter birth weight (16.99 vs. 16.16 kg) tended to be higher (Anil et al. 2010).

Figure 3. Organic trace mineral supplementation: Effect on litter size (n=15 trials)

Conclusions

Trace minerals have a major impact at all stages of reproduction. The provision of trace minerals at the correct level and in their organic form is essential for the modern hyper-prolific sow. They have been shown to increase litter size, as well as to reduce lameness and premature culling. Furthermore, the quality of the piglet at birth and weaning is increased and this helps to reduce pre-weaning mortality and to increase piglet weaning weight.