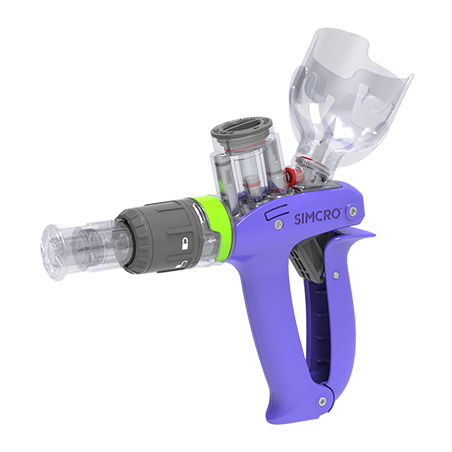

A large-scale commercial farm (>2000 sows) in eastern China reports an unusual condition of ocular opacity and blindness in several litters of suckling piglets. The sows are eating and milking normally. The number of stillborn and weak pigs is somewhat above normal and preweaning mortality is elevated. Blindness, corneal opacity, and swelling of the ocular area is observed in a few pigs in each of several litters. (Figure 1).

Affected pigs are depressed and lethargic and unable to nurse. The abortion rate is said to be somewhat elevated, but no outright abortion storms are observed. The number of mummified pigs is within normal parameters. No other clinical signs are reported. A quick check of breeding records seems to rule out a possible genetic cause, as unrelated genetic lines at the farm seem to be similarly affected.

Differential diagnosis includes porcine orthorubrivirus (Blue Eye Disease) and bacterial infection of the eye. Blue Eye Disease is caused by a paramyxovirus and is said to be endemic in parts of Mexico. It causes central nervous system disease, pneumonia, and reproductive problems in breeding swine, including orchitis and corneal lesions in boars, but has not been found in China or anywhere outside of Mexico. Preliminary diagnosis of Blue eye disease would be made by observation of the unusual clinical signs and confirmed by PCR and virus isolation.

Vitamin A deficiency could cause severe ocular lesions but is quite unlikely in this large commercial herd fed modern diets.

Diagnostics

One of the affected pigs is humanely dispatched and dissected by farm personnel. Fresh and formalin fixed tissues, (liver, lymph nodes, cerebrum), and the fresh eyes of the piglet in the picture (Figure 1) are submitted to the laboratory.

No gross pathology is noted by the farm personnel other than the ocular lesion. Intraorbital fluid aspirated from the eyes appears clear and unremarkable. Smears of the ocular fluid stained with Giemsa's stain reveal a few mononuclear cells and a few rod-shaped bacteria. A few unremarkable Escherichia coli are isolated from the ocular fluid. Likelihood of a bacterial cause is ruled out. The formalin fixed lymph node, brain, and liver are processed by a rapid paraffin method for tissue sections which are stained with H&E.

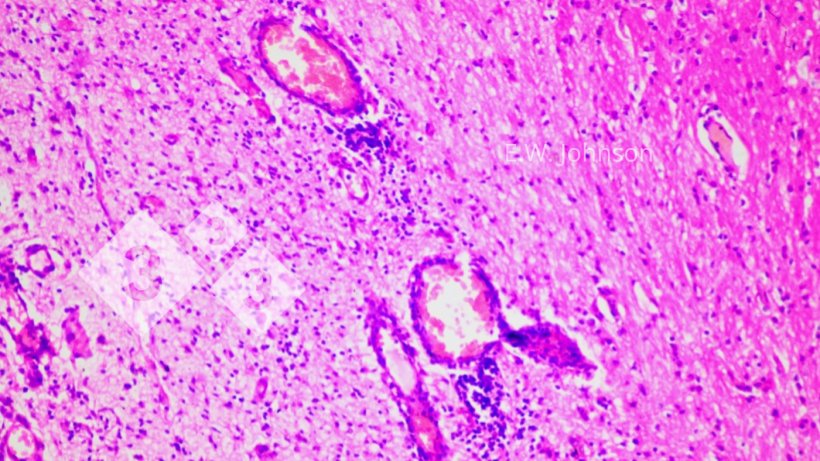

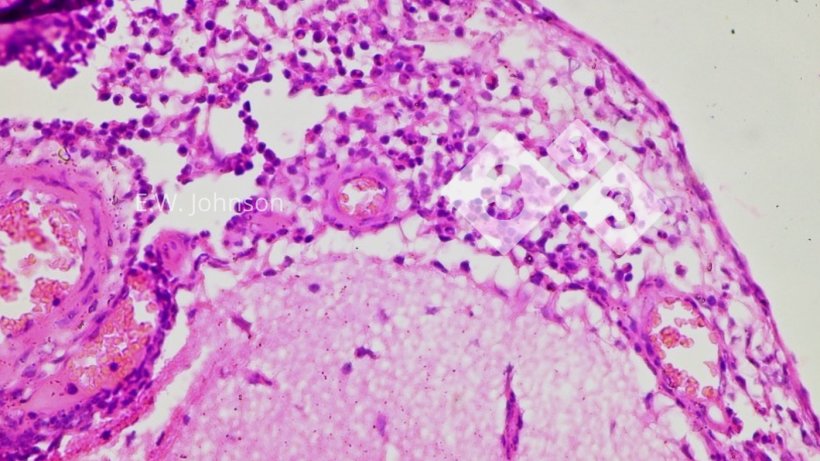

Microscopic examination of the brain reveals a meningoencephalitis with perivascular cuffing and gliosis, (Figure 2) and infiltration of the meninges with mixed mononuclear and polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells (Figure 3).

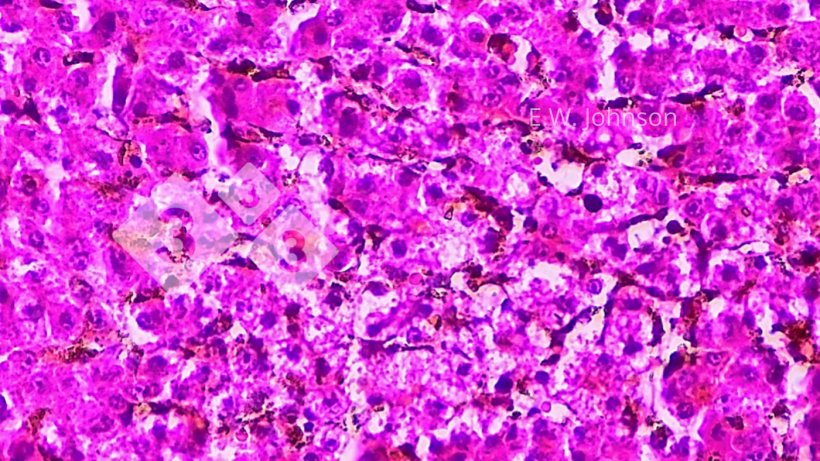

There is focal necrosis in the liver and the appearance of amphophilic intranuclear inclusions in the tissue surrounding the areas of necrosis (Figure 4). A presumptive diagnosis of pseudorabies (PRV, Aujeszky's Disease) is rendered.

PCR of the vitreous humour of the eye yields the amplified DNA of Suid alphaherpesvirus 1 (Pseudorabies) US8 (“unique-short” 8) gene encoding gE, (glycoprotein E) confirming the presence of wild-type pseudorabies virus. Sequencing of the amplified fragment of US8 reveals that the detected virus clusters with recent emerging variant strains of type 2 PRV common in China. (Figure 5.)

The herd was known to be seropositive for PRVgE antibody. Previously infected sows will be long-term seropositive for PRV gE and will pass the anti-gE Ab to their piglets making them PRV seropositive for up to 15 weeks of age. Therefore the Ab testing of young piglets is not useful for diagnosis of the disease where the sows are mostly seropositive. False positive diagnoses of PRV can made when there is not understanding of the persistence of maternal gE antibody.

Outcome

The farm indicated PRV positive gilts had entered the breeding herd and the threat of ASF had discouraged routine vaccination for pseudorabies. The fault in the PRV vaccination program was resolved and the farm has reported no further similar cases.

![Figure 5. PhyML Phylogenetic tree, PRV gE showing type1 (kaplan/becker -like) strains, "classical" type 2 (Fa/SC/Ea-like) strains , and enhanced virulence type2 (TJ/hb1201-like) strains. Recent PRV, this case [20-1048], and human encephalitis PRV hSD1-2019 are clustering with TJ/hb1201.](https://www.pig333.com/3tres3_common/art/pig333/18258/phyml-phlylogenetic-tree-prv-ge_244196.png?w=820&q=1&t=1653979446)

Discussion

Pseudorabies (PRV), also called "Aujeszky's Disease" (AD), was reported as a fatal neurologic disease of cattle in 1813 and was often mistaken for rabies in cattle and dogs. Due to the intense unstoppable pruritis produced by nerve damage in the itch circuitry, the condition was known as "mad itch" but it was also sometimes called "infectious bulbar paralysis". In the 1930's R. E. Shope reported that pseudorabies in Europe and mad itch in the US were the same disease and was widespread and endemic in swine in most pig producing countries.

The pig is the natural host of the PRV virus. Pseudorabies infection can be mild and nearly inapparent or can result in explosive outbreaks with high mortality. Variation in the observed virulence of PRV is the result of virus strain variation, animal factors and random factors.

The signs of PRV in breeding swine are respiratory disease and a viral reproductive syndrome with abortion, embryonic death, failure to give birth, mummification, weak pigs at birth, and infertility.

Ocular infection with PRV in pigs has not been previously reported.

Piglets less than 6 weeks of age may display neurologic signs, trembling, ataxia, convulsions, diarrhea, respiratory distress and high mortality. Piglets infected in the suckling period often have white foci of necrosis on the tonsils, liver, and sometimes the spleen. Older pigs generally display respiratory signs; coughing, dyspnea, and a generalized porcine respiratory syndrome when complicated by co-existing issues such as infection with mycoplasmosis, App, Strep, CSF, gastric ulcers, and ventilation faults. CNS (central nervous system) signs occasionally occur in growing pigs with PRV but rather rarely in breeding age animals. Hemorrhages may be seen on the kidney. PCV2, Classical swine fever (CSF), African swine fever (ASF), and PRRS might be included in a differential diagnosis or could be co-infections.

PRV is spread vertically by persistently infected sows, by fomites, dirty trucks and facilities, and by infected breeding animals. Infected growing pigs readily spread PRV by the respiratory route inside an air space. Aerosol transmission over distances of several kilometers may occur in cool moist air.

PRV can be observed in animals other than swine, particularly cattle, sheep, mink, dogs, and cats. Hatchling chickens are susceptible. Resistant farm dogs have been observed on PRV infected pig farms but dogs in general are susceptible and the outcome fatal after onset of CNS signs.

Should Aujeszky's Disease be considered to be a zoonosis?

Humans are relatively resistant. Human infection is extremely rare although the virus does replicate in cultured human cells. Human infection with mild clinical signs is reported from exposure to cats and dogs, with recovery of the virus and seroconversion. Recently, several serious cases of encephalitis and cases of endophthalmitis were documented in humans in China among pig caretakers, veterinarians, and slaughterhouse workers. Some history of injury or trauma is generally associated with such serious human infection. Virus detected in recent human PRV cases clusters closely with the PRV detected in this case (Figure 5).

Are good and effective vaccines available?

Vaccination is effective at reducing the severity and spread of PRV. PRV is eradicable with present technology but is endemic in most of the major pig producing provinces of China, with a herd-by-herd prevalence approaching 60% in high pig density areas. Killed (KV) and modified live vaccines (MLV) are available for use by China farms and most herds do vaccinate for pseudorabies. Most of the PRV vaccines in use worldwide carry a deletion in the gE gene rendering the vaccine avirulent in the case of the MLV and confer DIVA (differentiation of infected and vaccinated animals) capability. The first gE deleted vaccines were the Bartha small-plaque (K) avirulent live vaccine (1961) and the Bucharest (Buk) vaccine known as "Norden". PRV vaccines with complete or partial deletions of gE are in use. Used with a DIVA strategy and sanitation/isolation with all-in/all-out batch-type production, vaccine is a useful tool for elimination and eradication of pseudorabies. Pseudorabies vaccine does not induce sterilizing immunity nor does it create a "magic bubble" around the pig to shield him from infection under the vagaries of field conditions. However, sows that are repeatedly vaccinated for PRV predictably produce passive humoural immunity that protects their pigs from infection until well into the post-weaning period. Repeatedly vaccinated sows are unlikely to shed the PRV virus to their piglets or to incoming naive or quasi-naive gilts. Killed virus (KV) vaccines are more effective than MLV for booster immunization but experience has shown that MLV may be "good enough" as a booster in situations where a KV vaccine is unavailable. Where the gilts from vaccinated sows are vaccinated and reared in all-in/all-out batches and enter a vaccinated sow herd, they may remain negative and replace older infected sows by attrition. PRV has been eliminated in herds, areas and entire countries by this method.

Enhanced virulence pseudorabies

Since about 2011, "enhanced virulence" (EV) variants of pseudorabies have been reported in China. "Western" strains of PRV like Kaplan, Becker, and Bartha belong to the Type 1 group. (Figure 5) Note that Bartha K-61 has a complete deletion of gE. "Classical" China/Asia PRV {Ea, Fa, SC} are type 2. Variant Type 2 strains {TJ, hb1201, jsy7-2021, ...} are implicated in recent "enhanced virulence" pseudorabies outbreaks (with more severe pathology than classical type 2). PRV from human encephalitis/ophthalmitis such as GenBank: MT469550 (hSD1-2019) are clustering with the 20-1048 virus detected in this unusual case as well as EV strains. (Figure 5). Some of the enhanced virulence may be due to changes in gE glycoprotein for which Bartha-type deletion vaccines stimulate no immunity, or to changes at other loci.

Eradication of PRV is possible and feasible, has important implications in sustainability, food security, and human health, and would eliminate an important source of loss for the pig farms.