Changing from a liquid to a solid diet, the change of environment, and the establishment of a social hierarchy make weaning one of the critical moments in the life of a piglet.

The age and weight of piglets at weaning are the two factors that will determine the success of this phase and, especially, the management that needs to be implemented. Weaning weight is also a key piece of information on farrowing room performance.

In modern pig production multiple data are handled that allow us to analyse and understand the farm operation. For example, in sows: % returns, farrowing rate, total born and live born averages, etc. Also in the weaning or fattening phases: food conversion ratio, average daily gain, % deads, etc.

However, parameters based on average values do not give any information about data dispersion in our population. Knowing the dispersion is very important when evaluating the age and weight at weaning.

Let us imagine a farm with rooms for a five-week farrowing period:

In principle, we could say that farm weans piglets at four weeks, because the farrowing units, with a capacity for five-week farrowing periods, allow four-week lactation periods followed by one week for the depopulation and pre-farrowing phases. The truth is that if this farm weans once a week, there will be a dispersion of 7 days between the youngest and the oldest piglet (21-28 days).

Is this exactly what happens on farms? The answer is no.

The truth is that, today, genetic progress is achieving major improvements in litter size for sows. It is not uncommon to find farms averaging over 16 piglets born alive. In these situations the use of foster mothers is often required, as the number of piglets born exceeds the number of functional teats.

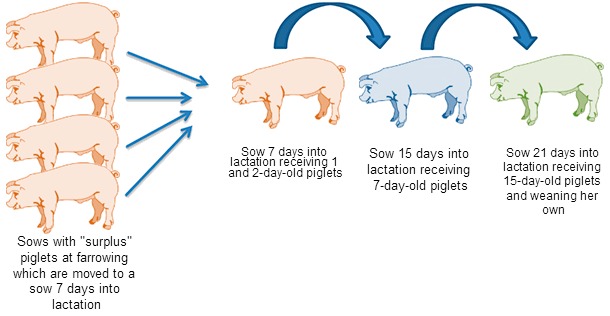

Photo 1: Although there are many ways to obtain foster mothers, the most common is to release a sow by weaning her piglets a week earlier, and then transfer piglets to her gradually, at 7 days intervals (3 steps), or even fostering 7-day piglets to a sow 21 days into lactation (2 steps)

The usual procedure involves weaning some piglets earlier.

A farm that uses 10% of foster mothers a week, ends up weaning over 30% of piglets one week earlier.

Similarly, the pressure on many farms to not wean piglets that do not reach a minimum weight, involves the creation of "repeaters". These are piglets than instead of being weaned at the standard age, stay another week in the nursery, either with their own mother or with a foster mother, in order to gain weight.

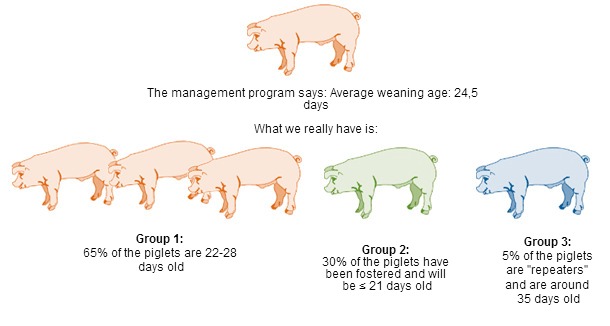

All in all, it is not surprising when the situation in many farms is very similar to the one illustrated below:

If we now look at the weaning weight, we notice that dispersion is usually high (Table 1.)

Table 1: Percentile considering an average weight of 6 kg, and a maximum age difference between piglets of 7 days.

10% of the piglets weight can be below 4.5 kg and another 10% above 7.5 kg.

| Percentile | ||||||||||

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | ||

| CV | SD | Live weight | ||||||||

| 20% | 1.2 | 4.50 | 4.88 | 5.25 | 5.63 | 6.00 | 6.38 | 6.75 | 7.13 | 7.50 |

Mike Brumm 2003

In a case like the one described here, we can easily find weights between 3 and 9 kg.

Furthermore, weight is not always a good indicator of age. With the age dispersion described, there will be heavy but young piglets (many of them in group 2) weight, and light "old" pigs (group 3).

Weight dispersion affects hierarchy —and therefore competition between piglets for resources like feed, water, place in the pen, etc.—, as well as weight dispersion as pigs are transferred to the fattening unit.

Age variability affects "maturation" of the piglet's digestive tract, the amount of creep feed ingested and therefore adaptation to solid feed.

How do we manage this variability?

Usual working procedures involve classification of piglets by size, aiming to minimize the negative impact of weight dispersion. Therefore, on arrival of a batch of weaned piglets, they are classified in various sizes: large, small, medium.

The main "differentiated" management measures applied to the weaning process are:

-

Feed presentation and management: additional feeding pans, wet feed, increased feed supply, etc. (Photo 2)

-

Kilograms of pre-starter offered to piglets: more kilograms for the smallest ones.

-

Environment: in case of several units, temperature for the smallest piglets is 1 °C to 2 °C higher.

Photo 2 The use of gruel or semi-moist feed favours early days feed intake and adaptation to solid feed

I recommend not to use piglet size as the only variable, and to identify piglets in groups 2 and 3 when receiving piglets in a nursery.

Tables 2 and 3 show the different management approach we would use in each case:

Table 2: If groups (g) 2 and 3 are not differentiated,

these piglets will not be managed differently from those of the same size but different age.

| Management depending on the group | Big 21-28 days (g1) |

Small 21-28 days (g1) |

Big < 21 days (g2) |

Small > 35 days (g3) |

| Adaptation to solid feed management | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Kilograms of pre-starter | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Environment | + | +++ | + | +++ |

Table 3: Once we differentiate piglets in groups (g) 2 and 3 from those in group 1, they can start receiving a specific, age-appropriate treatment. Fostered piglets, especially, can receive gruel and a little more pre-starter than if they were classified just as "large" piglets.

| Management depending on the group | Big 21-28 days (g1) |

Small 21-28 days (g1) |

Big < 21 days (g2) |

Small > 35 days (g3) |

| Adaptation to solid feed management | + | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Kilograms of pre-starter | + | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Environment | + | +++ | ++ | +++ |

Hyper-prolificity allows to wean more piglets per sow, but requires a more demanding management in the nursery, and increases weight and age dispersion at weaning due to the use of foster mothers. Differentiating younger fostered piglets and repeaters allows proper management of these piglets, reducing the number of poor doing piglets and improving their performance.