The previous article discussed the importance of excellent results in the first farrowing to place those sows on top of the production pyramid. To achieve this, it is up to us to offer the future sows an extremely high quality management in areas such as nutrition, health, handling, etc. Some factors however are, to some extent, beyond our control. One such factor is the weather, especially in Southern Europe, where temperatures are very high in the summer.

The effects of the weather on the results of the sow's services have been known for years, but... Can we minimize or overcome these negative effects? And, if there is such a possibility, has its effectiveness been evaluated?

The answer to both questions is yes.

The study on the prediction of the sows' future production based on their first farrowing results we talked about in our previous article (Ilida, Piñeiro and Koketsu, 2015), evaluates the impact of climate on the results of the first farrowing in Southern Europe. One of the most surprising facts emerging from this study is that the optimal age at first service depends on the time of the year the sow was born.

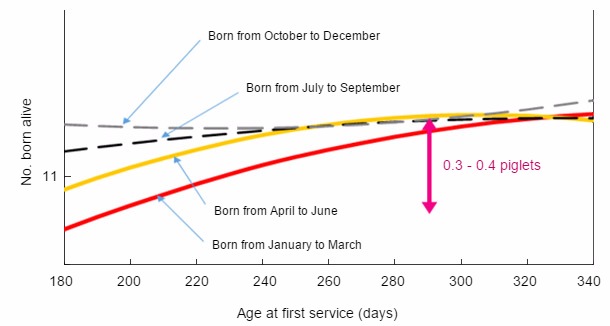

The bottom graph shows the relationship between age at first service and piglets born alive (PBA) at first farrowing in four groups of sows by month of birth of the sows:

- Group 1: sows born in the first quarter (January-March).

- Group 2: sows born in the second quarter (April-June).

- Group 3: sows born in the third quarter (July-September).

- Group 4: sows born in the last quarter (October-December).

To make it easier to understand the effects observed, we grouped the sows as follows: Sows born in the first half of the year (January-June) or the second half (July-December).

As shown in Figure 1, the number of PBA in sows born from July to December increases with age at first service, with up to 0.4 more PBA than sows serviced at the same age but born between January and June.

This effect is striking and has not been described previously. What might cause this improvement?

It is probably linked to the period of sexual maturation; the sows born between July and December will reach their sexual maturity in the cooler season (January-June) whereas the others will partially mature in the summer. Specifically, the sows born between January and March —hence reaching maturity in the hottest months—, are the ones with the worst results in terms of PBA in early service farrowings.

Based on this possible explanation, we can conclude —in a practical way— that it is important to take into account the time when sows reach sexual maturity and the period of preparation for service because, if it happens in the hottest months, the thermal stress associated with it and a probably lower intake of food result in a delay in both development and sexual maturation, which will in turn delay the optimal age for the first service.

Figure 1. Relationship between month of birth and age at first service, with piglets born alive at first farrowing.

To minimize this effect, the use of more concentrated diets for gilts that mature in the warmer months can also be considered, particularly for key nutrients. This, however, would require specific tests to determine the potential impact of this decision.

In short, this type of studies with large numbers of sows (109,373 sows in this case), can offer solid statistics on production trends or effects that, otherwise, could be easily missed.

Now that we know these production trends, we can use them to our advantage to get results at first farrowing of 15 or more live-born piglets, since these sows will be the ones with the longest life span and also the best returns.