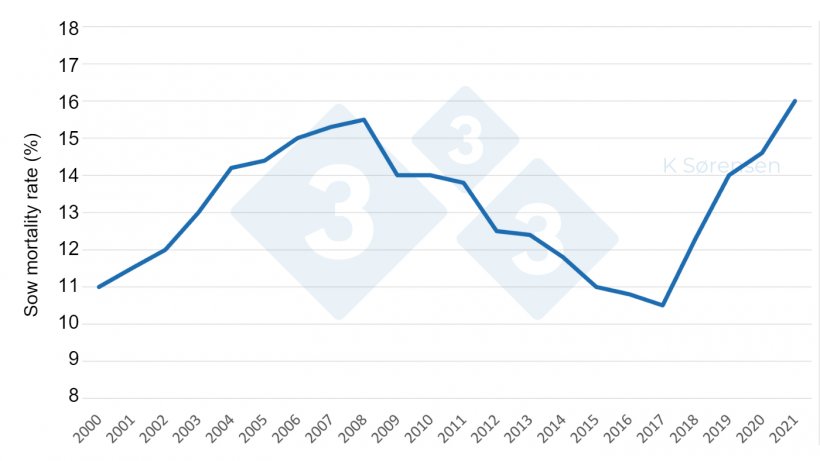

Rising mortality rates among sow herds have become a global cause for concern in recent years (Figure 1) (Sørensen and Thomsen 2017). Despite efforts to improve animal survival, the many challenges faced during the sow’s lifecycle make it difficult to break the trend. Even so, evidence is growing that a well-managed feed strategy is an important part of the solution (Stalder et al., 2004; Feyera et al., 2018).

For farmers, it’s an urgent problem. Apart from the immediate financial loss, poor sow survival indicates that animal welfare and productivity may be compromised – whether by a slippery floor or crowding in the barn or as an outcome of genetic selection. At the same time, farmers must continue to maximise their production efficiency to satisfy market demand for meat (AHDB 2021; Stein et al., 1990).

Market pressures on sow survival

High market demand has an inevitable impact on performance and longevity. Breeding programmes have both pushed up the number of live piglets born to each sow and the number that survive through weaning. In turn, sows must be able to utilise the full nutritional potential of the feed to ensure optimum milk production while maintaining their own physical health and growth.

Although survival rates vary from one country to the next, the reasons why sows have to be culled are roughly similar (Eckberg 2022; Stalder et al., 2004). One clear global trend is that survival rates are lower among young sows than older sows, with many sows being withdrawn from production after just one to three litters of piglets. Leg, reproduction and productivity problems are frequent causes. However, there is still a large number of sows that die suddenly of an unknown cause (Eckberg 2022; Hansen, 2022; Kongsted, 2019; Sørensen and Thomsen, 2017).

The difference in the feed

Experience shows that a good feed strategy makes an important difference to sow health and welfare and the opportunities to realise the full potential for long-term high production (Tybirk et al., 2014). While there will always be local differences in the available raw materials for feed, the need for high quality raw materials is a common denominator. In other words, raw materials must both be easily digestible and ensure the sow’s needs for protein and energy are fully met.

A sow’s lifelong high performance also depends on the feed’s content of vitamins and minerals, which play a key role in body functions, including enzyme systems, tissue functions and bone marrow. Minerals such as calcium, phosphorous and zinc are essential to building strong bones. As milk production relies on a steady mineral supply, an inadequate amount in the feed will result in depletion of the body’s own mineral depot – in this case, the bone mass (Sørensen, 2019). This increases the risk of leg problems that can cause a sow to be culled.

When making a feed strategy, one important risk factor to consider is mycotoxins, to which sows are especially sensitive. Present in various crops, the concentration of mycotoxins depends on the weather conditions in a given season. In sow feed, mycotoxins can have a considerable negative impact on reproduction and milk production in particular (Kanora and Maes, 2009).

Hallmarks of a good strategy

Regular feeding intervals are another essential aspect of a good feeding strategy (Stalder et al., 2004). Feed intake prior to farrowing, for instance, ensures sufficient energy and a stable blood glucose level. In addition to speeding up the farrowing process, a good energy supply helps ensure the last piglets in the litter are born in good condition, and furthermore reduce the number of stillborn piglets (Feyera, 2018; Oliveira et al., 2020).

The overall hallmarks of successful sow unit management are when milk production is optimal, piglet growth rates are high, and the sows remain strong and healthy with good potential for further production. Here, the thickness of the sow’s back fat is a key indicator of good condition and the ability to produce plenty of milk. At farrowing, the optimum back fat thickness is 14 to 17mm – and 13 to 16mm at weaning (Højgaard and Bruun, 2021). Excessive weight loss or loss of back fat can result in fewer piglets in the next litter. In other words, back fat needs to be maintained. Earlier feeding strategies have caused the gilts to be too heavy with a high meat percentage and low fat. To counteract this, there is a move towards lowering the feed’s protein content for the gilts combined with restricted feeding to reverse the recent trend of producing heavier sows with shorter longevity (Tybirk et al., 2014).

Shaping a positive trend

As global trends show, improving sow longevity and survival is no easy task. Numerous studies and tests have yet to find the solution. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that the answer rests with a long-term holistic approach, covering all factors that influence sow health, wellbeing and productivity.

A comprehensive feed strategy that meets changing nutritional needs throughout the sow lifecycle is a good place to start – combined with favourable living conditions that support health and welfare and a responsible breeding programme.