On 18 Jan 2018, one of ten expert panel discussions at the Global Forum for Food and Agriculture (GFFA) was held on Sustainable solutions to the livestock sector: The time is ripe! This two-hour session was organized jointly by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ), the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the Global Agenda for Sustainable Livestock (GASL) and the Livestock Global Alliance (LGA).

On 18 Jan 2018, one of ten expert panel discussions at the Global Forum for Food and Agriculture (GFFA) was held on Sustainable solutions to the livestock sector: The time is ripe! This two-hour session was organized jointly by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ), the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), the Global Agenda for Sustainable Livestock (GASL) and the Livestock Global Alliance (LGA).

This session was moderated by ILRI Assistant Director General Shirley Tarawali. Following a welcome by ILRI Director General Jimmy Smith, Stefan Schmitz, head of BMZ’s division of rural development and food security and commissioner for BMZ’s special initiative on One World–No Hunger, gave an opening speech. Fritz Schneider, chair of the Global Agenda for Sustainable Livestock (GASL), then gave a short overview of livestock and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, followed by a presentation by Kenyan Robin Mbae on livestock and climate change and a presentation by nutrition scientist Lora Iannotti on livestock and animal-source foods.

Shirley Tarawali then introduced the final speaker of this GFFA expert panel session. Emma Naluyima is a smallholder farmer and private veterinarian in Uganda who has integrated crop growing and livestock raising to build a thriving, profitable and environmentally friendly farm enterprise for her and her family.

‘I’m a smallholder farmer. It’s important that smallholder farmers integrate livestock into their farming. It’s feasible, productive and profitable. It’s made a difference to my life and family.

‘I did my master’s degree paying the tuition for my studies from the pigs that I reared. I’ve been able to take my children to very good schools. And I have a stable income. I own a car—a German car—made possible by livestock. And I was able to set up a school to continue passing on information to young children.

‘The founder of the Buganda kingdom, called Kintu, where I come from, kept livestock. Of all things in the world, he kept a cow. That cow enabled him to do integrated farming.

‘Today in Uganda and elsewhere, people use livestock not only for food and income, but also as a bank account and as insurance. They can sell their cattle to take their children to school. They can sell their cattle to get medical attention. And in the eastern part of the country, if you don’t have cattle you cannot marry a girl. So cattle, and livestock in general, are very, very important.

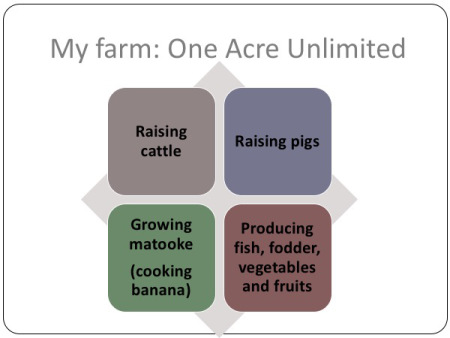

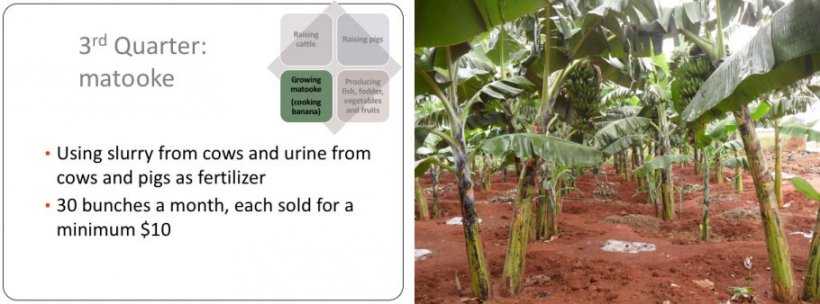

‘Here’s how it works for me and my family. My farm is called ‘One Acre Limited’. I divided it into quarters. On one quarter, I keep pigs. On another quarter, I keep cattle. On a third quarter, I grow matoke, or cooking banana. And on the other quarter, I grow fish, fodder for the animals and vegetables and fruits.

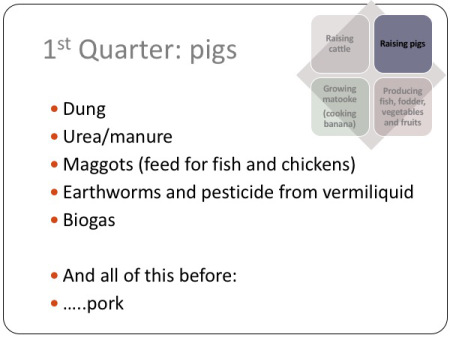

‘Pigs are my favourite animal. I feel cheated if I am not introduced as ‘Mama Pig’. That’s because I’m standing here today not because I’m a vet but because I’m a farmer—a pig farmer.

‘In this quarter where I grow pigs, I use the urine from the pigs as urea fertilizer. I use the pig dung to produce maggots that feed my fish and chickens, to grow earthworms and to produce biogas.

‘I do all this before I produce the pork. My pigs eat fodder that I grow on the farm.

‘Left is the urine we collect from the pig house and take to the garden. The ammonia in this urine helps repel pests from my plants. And right is pig dung, which is “green gold”. This is where my money comes from before I get pork. I would be grateful to any scientist who could make me diapers for pigs—because I don’t want to lose a speck of pig dung!

‘We collect the pig dung and use it to feed houseflies, which in turn produce larvae, or maggots, that we use to feed the fish and chickens. These maggots comprise 65% crude protein, which is higher than the protein content of our other animal feeds. My chickens grow faster when feeding on the maggots: in four weeks I can produce a chicken weighing 1.5 kilos rather than 1 kilo.

‘These are my lovely local chickens. In my local area, these might be thought to be one year old, but these birds are just 3–4 months old. I spend nothing to feed my chickens. It’s my pigs that are doing this. And then at the end of the day I get very nutritious, very yellow-yolked, eggs.

‘After we’ve collected all the maggots from the pig dung, we introduce earthworms and then they feed on the pig dung and reproduce and create soil, which I sell and make money from as well. The earthworms excrete a liquid that I use as a fertilizer and as a pesticide that repels aphids and nematodes. And of course the fish feed on the earthworms.

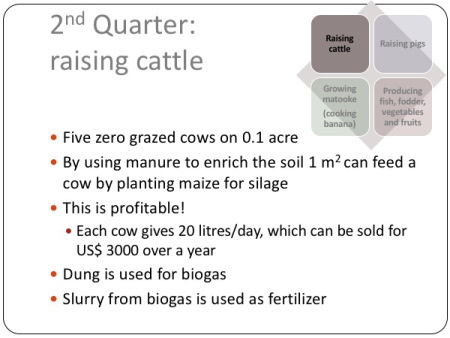

‘In the second quarter of my one-acre farm, I keep five zero-grazed cattle (my target is 10–15 cows). Each cow gives me on average 20 litres of milk a day. I sell the milk and earn about USD3,000 a year. I use the cow dung to produce biogas and the slurry from the dung to fertilize my maize crop and to make silage. This is very profitable. I don’t have to spend money buying inorganic fertilizer.

‘These are some of my cows. Left is a Guernsey-Jersey cross eating hay, right are Holstein-Friesians eating hydroponic fodder.

‘And above is the anaerobic digester I use to produce biogas. Back home, almost everyone has a charcoal stove or uses firewood for cooking. I don’t use either. I just use biogas. You can see how clean this saucepan is above (you can think it’s German!). When we use a charcoal stove or firewood, we are cutting down trees, So my livestock help me to reduce both deforestation and climate change.

‘The slurry that comes from the biogas is what I use on my third quarter, the banana plantation, which gives us our staple food.

While the staple food of Germany may be sausages and pork, the staple food of my home is the cooking banana, called ‘matoke’, From this quarter of my farm I get about 30 bunches of banana. I put my manure on the plantation soil to produce those very big bunches. Before I came here last Saturday, I harvested a bunch of matoke that weighed 95 kilos. I sell the matoke for Uganda shillings 1,500 per kilo (so do the maths!).

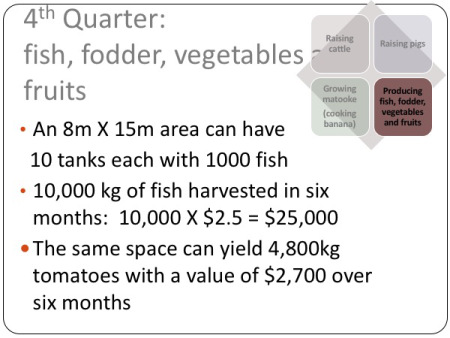

‘On my fourth quarter of land, I grow fish, fodder, vegetables and fruits. In a space of 8 by 15 metres, I can harvest 10,000 kilograms of fish in six months, generating on average about USD25,000 in six months. And if I’ve not used commercial feed but rather maggots and earthworms from pig manure, I reduce my costs of fish production by three-quarters and get the fish ready for market in 4 rather than 6 months. The same space can yield about 4,800 kilograms of tomatoes over 6 months, for a value of USD2,700.

‘This is my greenhouse. It’s all makeshift—just wood and polythene bags and water.

‘These are the tomatoes and the vegetables, red cabbage, green cabbage.

‘And passion fruit. In my house, what makes my marriage is that I don’t leave home until I’ve made 5 litres of passion fruit juice for my husband, and that’s thanks to the cow dung that I use to make sure that I have passion fruit.

‘I started today by saying that smallholder crop farming that integrates livestock is feasible, productive and profitable—that it’s made a difference to my life and family. For my master’s degree, I had to pay USD4,000 a semester. That was a lot of money for me. I did it by selling my pigs.

I’m standing here today because of the pig.

That’s incredible.

And true.

‘Finally, research solutions and training both need to be shared more widely. Because my husband and I have learned a lot from farming, we decided to create a primary school to provide a foundation for local children. The school is now running with 200 children. We are teaching three things I learned from farming that I think Africans are failing to teach their children: time management (farming demands the greatest time keeping!), the value of money and the culture of saving.

‘This is my school. And these are the kids we teach.’

March 7, 2018 - ILRI